| < | Wavepacket Blog only displaying 'economics' posts |

> |

| << Newer entries << | |

| 2010 | |

| January | |

| Sun Jan 10 23:20:41 2010 Why was there a worldwide recession? |

|

| 2009 | |

| December | |

| Sun Dec 27 23:34:18 2009 Personal Finance Platitudes |

|

| November | |

| Wed Nov 4 22:47:02 2009 Yay! More torture. |

|

| >> Older entries >> | |

| >> links >> | |

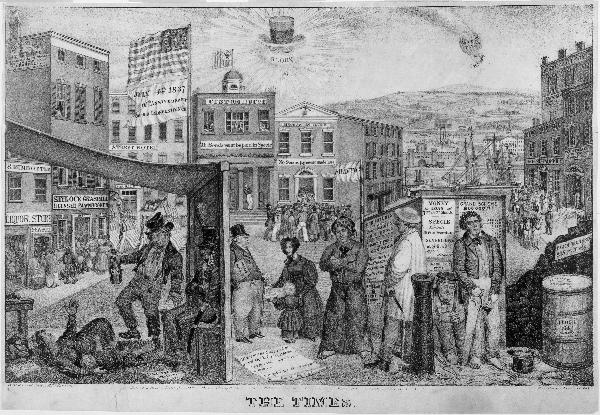

| Sun Jan 10 23:20:41 2010 Why was there a worldwide recession? Oddly, no one agrees on this. Worse, no one agrees with me. |

|

| I happened to be reading through

Slate, one of my favorite websites. I saw that they had an article covering

the 15 best explanations for the Great Recession.

The author's contention is that although most people seem to agree that the mortgage collapse precipitated the crisis, no one agrees on why the fallout was so bad. Jacob Weisberg's conclusion: our financial markets need stronger regulatory supervision and better controls to prevent bad bets by big firms from going viral Usually I like Slate, but this time they seem to have watered down the subject matter so much that the article is actually misleading. To be fair, Weisberg was writing the article for Newsweek (sorry, couldn't resist the jab). Saying "the reasons for the recession are very complicated" and "the solution is more regulation" is basically a capitulation. The author is admitting that he doesn't actually know what went wrong, but is sure someone does, and that someone will regulate things better so that this never, ever happens again. Of course, they said that in the Panic of 1837, the Panic of 1857, the Panic of 1873, the 1882-1885 recession, and... well, you get the idea. If you didn't get the idea, you can peruse Wikipedia's list of US recessions. Don't get me wrong, I'm not a laissez-faire capitalist. Directed regulation is effective and required. But on the other hand, I'm not a wild fan of wishful naivete either. Vague hopes that increased regulation are going to somehow prevent future recessions are frankly stupid. At least admit that you don't know what went wrong, and don't try to fix things until you do. Being all-knowing, or at least partially knowing and both tired and cranky, I can offer my own suggestions. The first step in understanding what went wrong is to remember that, unlike what most columnists are saying, the root cause of recessions is pretty straightforward. Why do recessions happen? Generally, because people spent more money than they actually had. That's called a boom period. Then the bills show up, people realize the assets they were counting on weren't worth as much as they thought, and prices and spending generally contract for a while as everyone sorts out the mess. You can change the exact flavors of the day, but that's basically it. People spend too much, either because of cheap money (interest rates too low) or overvalued commodities (mortgages not properly valued for risk), and then when reality hits they have to spend less for a few years to even everything out. And boom and bust cycles will always be around, because accurate valuation for anything is very hard and even honest, diligent people get it wrong most of the time. So that's part of the problem (or the reality). Boom and bust cycles will always be here, and therefore, there will always be recessions of some kind or another. So what does regulation do? More importantly, why is regulation around? Regulation exists for only one reason: to reduce risk. A great example is the regulation banks must undergo for FDIC insurance. Having FDIC insurance is great for depositors, but a bank can't promise that to customers until they first prove to the FDIC that they are running a low-risk operation. The government can't insure accounts if the risk is too high. And don't fool yourself: regulation cannot remove risk. Even the most stringent accounting and ethical behavior can't protect a company from competing innovation, freak weather, or an asteroid impact. All regulation can do is attempt to reduce risk. And if regulation can only reduce but not eliminate risk, then recessions will continue to happen. So why was this recession worse than most others, historically speaking? One reason, I think, is the repeal of the Glass-Steagall act. I'm not a banking expert, and I certainly don't commonly quote banking regulations. But I keep coming back to this one. The Glass-Steagall act was passed in 1932 to keep banks simple. The act said that commercial banks (where people and businesses keep their accounts) cannot engage in investment banking (where the bank uses peoples' deposits to fund speculative investments). As I said, that was repealed in 1999 and now there are no distinctions between commercial and investment banks (at least in this sense). Your bank can take your savings account and invest it in speculative ventures. So when the Aughties Recession (or the Great Recession) started, more of the nation's money (our savings accounts) were exposed. Whether it was an over-reliance on new mortgage securities or otherwise, the large amounts involved meant more people's cash was at risk, and more money was frozen when people were afraid to sell. So what is my solution? Keep regulation simple. Re-instate the Glass-Seagall act, and regulate commercial banks with simple (or at least standard) accounting and financial instruments. Most importantly, guarantee all money that is regulated. And if you're not going to guarantee an institution or account, don't regulate it. That tends to be a great focuser. Require honesty and accuracy in accounting in all banks and companies, but don't pretend to certify that high-risk investments are safe or understood. Instead, make the risks known and make sure everyone knows which accounts are guaranteed, and which aren't. Comments |

Related: > economics < Unrelated: books energy environment geopolitics lists mathematics predictions science |

| Sun Dec 27 23:34:18 2009 Personal Finance Platitudes Short sayings I wish I'd learned earlier. |

|

| I was just going through my finances again after the Holidays. Always

interesting to see how the final numbers turned out!

As part of that, I happened to catch a good article about paying cash for everything to avoid accumulating debt. I think I'm pretty careful about how I spend but I learned a lot from that article. The article made me think of all the money management platitudes out there. Many of them are bogus, I'm sure. But these are the ones I think are actually pretty helpful: Never borrow to consume, only borrow to invest.This is great advice. (Amazingly, after taking economics in high school and college, I only heard about it years later while reading an otherwise low-value book about the American federal deficit.)I had usually avoided financing plans for random purchases like TVs or furniture, but hadn't thought about it much. This rule is why. And like the article above, the main point is to pay cash for most everything. Because of this I've been much better about putting less purchases on my credit card, and paying it off completely each month. Don't put all of your eggs in one basket.This is a basic rule, but people seem to forget it all the time. Just do a simple search for people that have lost their life savings somehow. (Interesting that many of the latest search results are victims of Bernie Madoff!)I feel terrible for anyone that loses their life savings due to a single event, and I hope Madoff's victims are able to recover some of their savings. But let's not forget: putting all of your savings or investments in one place is asking for disaster. Reading through some of those search results is pretty scary, with stories like this guy. The author doesn't sound like a moron. He and his wife sold their property at the peak of the market, and obviously had a fair amount of money from other investments. Yet they inexplicably put all of it into one person's hands, and then it was all lost. I feel absolutely terrible for them. I guess this platitude ("Don't put all of your eggs in one basket") is known by everyone but is often hard to follow in practice. Even forgetting about nefarious financial advisors, people make basic mistakes like keeping all of their stock and/or pension with their employer--this means a single company is paying their salary and responsible for their retirement nest egg! You can imagine what happens to them when the employer goes under. Even more so when both husband and wife work for the same company, and have their stock and pension with the company. That's happened to people at Enron, Arthur Anderson, and Lehman Brothers. These are firms that hired smart people! But they put all of their eggs in one basket. So I've gone through and made sure my savings are diversified. And as much as I love the company I work for, I make sure my company stock doesn't become too large a fraction of my savings. Keep your age in bonds.Okay, this one isn't as useful day-to-day. But I found it remarkable because it was succinct and very specific.This was a new one to me, but a pretty good one. If you've got any sort of 401(k) or other savings, make sure a healthy percentage of it is out of the stock market. Put that money in cash or bonds instead. I knew that, but somehow it wasn't until recently that I heard to use your age as a rule of thumb for the percentage. I had been using 20% as a rough guess, but for 2010 I'll gradually bump that up to around 40% (guess my age!). Comments |

Related: > economics < lists Unrelated: books energy environment geopolitics mathematics predictions science |

| Wed Nov 4 22:47:02 2009 Yay! More torture. More notes on the economics of torture. |

|

| In May, I tried to make

the case for disallowing torture of suspects, even (gasp) terror suspects.

At the time, the torture memos were making the headlines, and as a result many people were asking if and when torture was ever appropriate. In fact, people started re-examining a number of moral issues in combat against terrorism. Here are some of the better articles I ran across. First, this article from Slate documents the current legality of assassination. This is from Slate's "Explainer" series, which is fascinating but purposely sticks to the facts. That's fine: the whole point of this article is to call out the supposed legality (or not) of political assassinations. Certainly President Ford's 1976 Executive Order banning assassination is the starting point. (By the way, that's a surprisingly readable document!) The point of the Slate explainer article was that although killing heads of state is clearly off-limits, targeting terrorists or "part time" combatants is much more problematic. Curiously, the Slate explainer article doesn't say so explicitly, but killing suspected al-Qaida members in CIA-sponsored Predator attacks would also seem to be illegal. Now that the CIA has terminated its al-Qaida assassination authorization, perhaps the US and other intelligence agencies will capture or disrupt terrorist organizations without killing suspects? A harder mission, but keeping the high moral ground is much more honorable and probably more effective. Why do I say that? Well, for one thing, there is a chance that torture makes the FBI's job harder, because the agency will have a harder time cultivating double agents. The argument is that engaging in torture "casts doubts on the U.S. government's overall willingness to act in good faith." I'm guessing most terrorists are irrational, and won't care whether we torture or not. But many of these potential double-agents are fairly rational people ("diplomats, scientists, or scholars"), not terrorists, and so the high moral ground may actually make a difference in the FBI's ability to turn foreign agents. Most interesting of all was an article by a former legal advisor to the Israeli Defense Forces, who had made frontline decisions about "targeted kills." That's kind of an euphemism for assassination, but the author believed there was a distinction between political assassination (targeted kills by nonmilitary, nonuniformed agents) and targeted kills made by uniformed military personnel in a combat zone. The author advised Israeli military commanders (in the field) from 1994 to 1997. To my civilian mind, the author's viewpoint was somewhat brutal. As he ends his article: ... if you're sure you've got the right guy, and you have no other viable options, fire away. The nation's safety may depend on it. This reminded me of situations the Slate explainer called "[adopting] a classic aspect of law-enforcement philosophy to justify an otherwise blatantly criminal action." But this really all comes down to whether or not self defense is justified. And that is an especially hard problem in combat zones. But for all of his at-times hawkish tones, the Israeli military advisor was pretty harsh about the US Administration's authorization of al-Qaida assassinations. As the author put it: Counterterrorism, in civil democratic regimes, must be rooted in the rule of law, morality in armed conflict, and an analysis of policy effectiveness. There can be no "ifs, ands, or buts." Even a hawk on the front lines of an anti-terrorist war takes a hard line on law and morality! But after all, that is a good deal of what he is fighting for. I think whether or not the nation supports assassination or torture depends on the current emotional state. If there is another terrorist attack, the majority will certainly accept (if not demand) targeted killings of suspects without trial--at least for a while. But the current less-passionate debate, from a number of sources, would indicate that torture and assassination--any methods of dubious morality--are probably self-destructive in the long run. Comments |

Related: > economics < geopolitics Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics predictions science |

| Links: |  |

Blog Directory | Blog Blog | Technorati Profile | Strange Attractor |