| < | Wavepacket Blog only displaying 'geopolitics' posts |

> |

| << Newer entries << | |

| 2011 | |

| February | |

| Tue Feb 8 22:51:24 2011 Free Internet |

|

| January | |

| Thu Jan 27 22:35:37 2011 Upheavals in the Middle East |

|

| 2009 | |

| November | |

| Wed Nov 4 22:47:02 2009 Yay! More torture. |

|

| >> Older entries >> | |

| >> links >> | |

| Tue Feb 8 22:51:24 2011 Free Internet More thoughts on free Internet... |

|||||||||

| In my previous post (

Upheavals in the Middle East) I mentioned my crazy idea for giving free Internet connections (and smart

phones) to people in repressive regimes. The idea is that by having the the

ability to communicate with each other and the outside world, people in those

countries would be able to avoid one of the chief tools of repression: limited

access to information.

Also, within repressive regimes, access to communications and outside information can itself be an agent for change and improvement--and even revolution. Witness how Tunisia and Egypt both attempted to crack down on the Internet during the recent protests, with Egypt going to particular extremes. In fact, Egypt cut off Internet access just as I was posting my blog entry about using the Internet as an asymmetric attack against repressive regimes! Talk about coincidences. Yesterday Slashdot had a link to a story about how the US has secret tools to force Internet on dictatorships (which references a Wired story as the primary source), which I thought was awesome timing given my blog post! Obviously both Wired and Slashdot read my blog a lot. However, the story isn't quite what I was thinking. The Wired story talks about how the US Gov't could take out foreign computer networks (hardly news) or even restore some Internet service to localized areas via flying networks or satellite dish drops. All in all, I found it pretty underwhelming, and small-scale. Plus, as the article noted, flying our own aircraft in someone else's airspace could be construed as an act of war, even if we were just flying Internet relay stations. No, it's way better to go the full deal. Set up satellite-based internet, using satellite-enabled smart phones or routers. Then people could get access to the Internet, and communicate with each other, without us having to invade peoples' air space. In fact, we could just provide satellite-based Internet hubs, and people could use their own smart phones. That would be more flexible and cheaper. [Providing a satellite network does raise the problem of antisatellite weapons, but having satellites isn't by itself an act of war.] Would providing a satellite-based Internet for North Korea, China, or Myanmar be expensive? Sure, maybe billions of dollars a year. But a war costs billions of dollars a week. So providing free satellite-based Internet to repressive regimes could be even more effective, at a fraction of the price, not even counting the lives saved. Comments |

Related: economics > geopolitics < Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics predictions science |

||||||||

| Thu Jan 27 22:35:37 2011 Upheavals in the Middle East How will this all work out? |

|||||||||

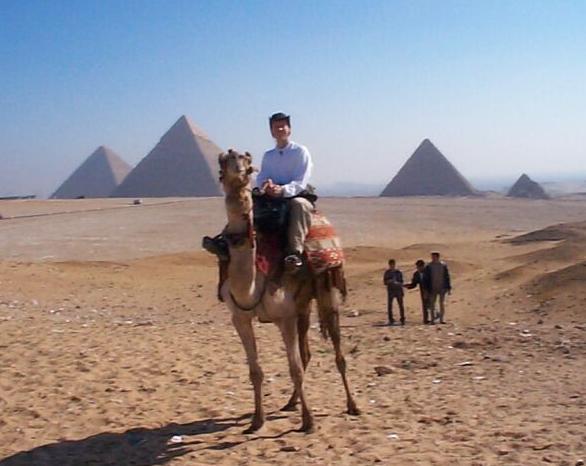

| One of my favorite trips ever was a

2001 trip to Tunisia, almost ten years ago exactly. At the time, it struck me as almost the perfect

country: a perfect climate, beautiful seashores, a range of terrain including mountains and

deserts, great people, great food, and fun driving.

And there were amazing Roman ruins scattered throughout the country. Most of all, I was impressed by the people. I was a westerner travelling alone in a predominantly Muslim country (this was pre-9/11), but I really never felt uncomfortable, especially once I was out of the grittier parts of Tunis. The countryside was beautiful, and the people were generous and friendly. It reminded me more than any other trip how alike people really are, no matter the country. Now, of course, Tunisia is in the news due to the recent riots and general unrest that caused the downfall of the regime and the flight of their President. Even in 2001, I noticed that Ben Ali wasn't much liked:

And I also noticed the unemployment and dissatisfaction, which a fellow traveler Smith and I commented on:

Well, it looks like people stopped drinking and smoking. And now the Tunisian disturbance has spread to Egypt and Yemen at least. How far will this go, and where will it end? Hopefully this will end up with all of the repressive governments of the Middle East being replaced by more representative governments that respect individual rights and freedom of expression. But I don't think it will. Instead, I think only a few countries--the poorest ones--will see revolts. Egypt, Yemen, and Tunisia are obvious candidates. Countries with a lot of oil--and oil money--likely won't see these sorts of uprisings, since they have more content citizens, and larger security forces. So the richer repressive governments will be fine. Even in the countries that do revolt, will democracy take root? Will we see a flourishing of individual rights and freedoms in the Middle East? Again, I hope so, but I wouldn't bet on it. The main reason I don't think so is that these riots are creating power vacuums. There is no credible democratic opposition in Tunisia, Yemen, or Egypt. Instead, various fringe power groups will try to take control. Even worse, Western countries have a poor image in these countries, and many of the hated regimes had at various points attempted to Westernize. So a shift to supposedly "western" values such as individual rights or democracy could easily be twisted by demagogues to appear as non-patriotic! This problem of a power vacuum was first really studied during the French Revolution. In fact, the French Revolution was studied and used as a template for action by the Bolsheviks when they seized power after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The result of the French Revolution? The Reign of Terror, culminating in Bonaparte's dictatorship. It took many years--a generation--before the Republic gained its footing. The result of the Russian Revolution? The Red Terror and Communism, which didn't really fall until 1990. In fact, there are very few examples of revolutions leading to democracies that champion individual rights, and they all seemed to involve politically powerful or influential pro-democatric factions involved from the start. So I am not optimistic about prospects for democracy and individual freedoms in the Middle East in the near term. There is one chief learning through all of this that I hope pro-democracy countries take note of. That is the role of the Internet in the upheavals. It was the ability of people to communicate events and plan across entire countries at once that made the uprisings so effective and total. I've had this crazy idea for a while, so I'll mention it now: pro-democracy countries should fund smartphone networks that cover repressive autocracies. We (the world's pro-freedom countries) should build out the networks, and provide hardware, for citizens of countries who are denied freedom of speech. We could even give away the smartphones to citizens for free, through airdrops or other delivery methods. We'd want to ensure that the majority of the smart phones reached real citizens, and not the regime. And our control of the network would mean that citizens could communicate with each other and the rest of the world without the regime intercepting, blocking, or listening to the messages. This would cost billions, but would be far cheaper than troops on the ground, and maybe more effective. It is also a beautiful asymmetric attack. If a repressive regime retaliated by building a free smart phone network for us, I think we would welcome it. Tell your congressman about this idea. We should give away smart phones and operate networks that cover the world's repressive regimes! But in the meantime, pray for the people of the countries that are rioting, and hope they get better governments than what they have now. I think the best action we as outsiders can take is to ensure that all of those involved are able to communicate with each other and the outside world. Comments |

Related: economics > geopolitics < predictions Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics science |

||||||||

| Wed Nov 4 22:47:02 2009 Yay! More torture. More notes on the economics of torture. |

|||||||||

| In May, I tried to make

the case for disallowing torture of suspects, even (gasp) terror suspects.

At the time, the torture memos were making the headlines, and as a result many people were asking if and when torture was ever appropriate. In fact, people started re-examining a number of moral issues in combat against terrorism. Here are some of the better articles I ran across. First, this article from Slate documents the current legality of assassination. This is from Slate's "Explainer" series, which is fascinating but purposely sticks to the facts. That's fine: the whole point of this article is to call out the supposed legality (or not) of political assassinations. Certainly President Ford's 1976 Executive Order banning assassination is the starting point. (By the way, that's a surprisingly readable document!) The point of the Slate explainer article was that although killing heads of state is clearly off-limits, targeting terrorists or "part time" combatants is much more problematic. Curiously, the Slate explainer article doesn't say so explicitly, but killing suspected al-Qaida members in CIA-sponsored Predator attacks would also seem to be illegal. Now that the CIA has terminated its al-Qaida assassination authorization, perhaps the US and other intelligence agencies will capture or disrupt terrorist organizations without killing suspects? A harder mission, but keeping the high moral ground is much more honorable and probably more effective. Why do I say that? Well, for one thing, there is a chance that torture makes the FBI's job harder, because the agency will have a harder time cultivating double agents. The argument is that engaging in torture "casts doubts on the U.S. government's overall willingness to act in good faith." I'm guessing most terrorists are irrational, and won't care whether we torture or not. But many of these potential double-agents are fairly rational people ("diplomats, scientists, or scholars"), not terrorists, and so the high moral ground may actually make a difference in the FBI's ability to turn foreign agents. Most interesting of all was an article by a former legal advisor to the Israeli Defense Forces, who had made frontline decisions about "targeted kills." That's kind of an euphemism for assassination, but the author believed there was a distinction between political assassination (targeted kills by nonmilitary, nonuniformed agents) and targeted kills made by uniformed military personnel in a combat zone. The author advised Israeli military commanders (in the field) from 1994 to 1997. To my civilian mind, the author's viewpoint was somewhat brutal. As he ends his article: ... if you're sure you've got the right guy, and you have no other viable options, fire away. The nation's safety may depend on it. This reminded me of situations the Slate explainer called "[adopting] a classic aspect of law-enforcement philosophy to justify an otherwise blatantly criminal action." But this really all comes down to whether or not self defense is justified. And that is an especially hard problem in combat zones. But for all of his at-times hawkish tones, the Israeli military advisor was pretty harsh about the US Administration's authorization of al-Qaida assassinations. As the author put it: Counterterrorism, in civil democratic regimes, must be rooted in the rule of law, morality in armed conflict, and an analysis of policy effectiveness. There can be no "ifs, ands, or buts." Even a hawk on the front lines of an anti-terrorist war takes a hard line on law and morality! But after all, that is a good deal of what he is fighting for. I think whether or not the nation supports assassination or torture depends on the current emotional state. If there is another terrorist attack, the majority will certainly accept (if not demand) targeted killings of suspects without trial--at least for a while. But the current less-passionate debate, from a number of sources, would indicate that torture and assassination--any methods of dubious morality--are probably self-destructive in the long run. Comments |

Related: economics > geopolitics < Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics predictions science |

||||||||

| Links: |  |

Blog Directory | Blog Blog | Technorati Profile | Strange Attractor |