| < | Wavepacket Blog only displaying 'geopolitics' posts |

> |

| << Newer entries << | |

| 2011 | |

| January | |

| Thu Jan 27 22:35:37 2011 Upheavals in the Middle East |

|

| 2009 | |

| November | |

| Wed Nov 4 22:47:02 2009 Yay! More torture. |

|

| May | |

| Wed May 6 22:41:32 2009 Is Torture Worth It? |

|

| >> Older entries >> | |

| >> links >> | |

| Thu Jan 27 22:35:37 2011 Upheavals in the Middle East How will this all work out? |

|||||||||

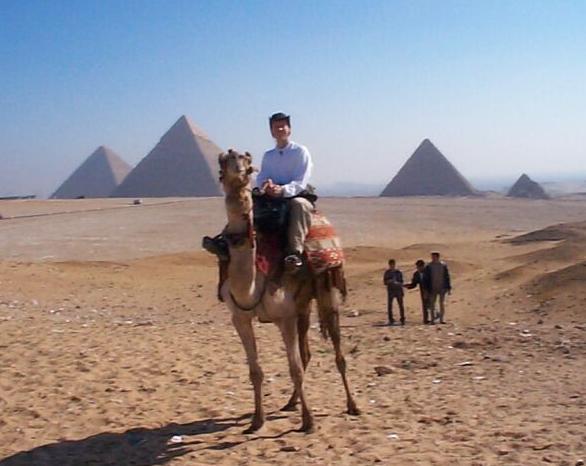

| One of my favorite trips ever was a

2001 trip to Tunisia, almost ten years ago exactly. At the time, it struck me as almost the perfect

country: a perfect climate, beautiful seashores, a range of terrain including mountains and

deserts, great people, great food, and fun driving.

And there were amazing Roman ruins scattered throughout the country. Most of all, I was impressed by the people. I was a westerner travelling alone in a predominantly Muslim country (this was pre-9/11), but I really never felt uncomfortable, especially once I was out of the grittier parts of Tunis. The countryside was beautiful, and the people were generous and friendly. It reminded me more than any other trip how alike people really are, no matter the country. Now, of course, Tunisia is in the news due to the recent riots and general unrest that caused the downfall of the regime and the flight of their President. Even in 2001, I noticed that Ben Ali wasn't much liked:

And I also noticed the unemployment and dissatisfaction, which a fellow traveler Smith and I commented on:

Well, it looks like people stopped drinking and smoking. And now the Tunisian disturbance has spread to Egypt and Yemen at least. How far will this go, and where will it end? Hopefully this will end up with all of the repressive governments of the Middle East being replaced by more representative governments that respect individual rights and freedom of expression. But I don't think it will. Instead, I think only a few countries--the poorest ones--will see revolts. Egypt, Yemen, and Tunisia are obvious candidates. Countries with a lot of oil--and oil money--likely won't see these sorts of uprisings, since they have more content citizens, and larger security forces. So the richer repressive governments will be fine. Even in the countries that do revolt, will democracy take root? Will we see a flourishing of individual rights and freedoms in the Middle East? Again, I hope so, but I wouldn't bet on it. The main reason I don't think so is that these riots are creating power vacuums. There is no credible democratic opposition in Tunisia, Yemen, or Egypt. Instead, various fringe power groups will try to take control. Even worse, Western countries have a poor image in these countries, and many of the hated regimes had at various points attempted to Westernize. So a shift to supposedly "western" values such as individual rights or democracy could easily be twisted by demagogues to appear as non-patriotic! This problem of a power vacuum was first really studied during the French Revolution. In fact, the French Revolution was studied and used as a template for action by the Bolsheviks when they seized power after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The result of the French Revolution? The Reign of Terror, culminating in Bonaparte's dictatorship. It took many years--a generation--before the Republic gained its footing. The result of the Russian Revolution? The Red Terror and Communism, which didn't really fall until 1990. In fact, there are very few examples of revolutions leading to democracies that champion individual rights, and they all seemed to involve politically powerful or influential pro-democatric factions involved from the start. So I am not optimistic about prospects for democracy and individual freedoms in the Middle East in the near term. There is one chief learning through all of this that I hope pro-democracy countries take note of. That is the role of the Internet in the upheavals. It was the ability of people to communicate events and plan across entire countries at once that made the uprisings so effective and total. I've had this crazy idea for a while, so I'll mention it now: pro-democracy countries should fund smartphone networks that cover repressive autocracies. We (the world's pro-freedom countries) should build out the networks, and provide hardware, for citizens of countries who are denied freedom of speech. We could even give away the smartphones to citizens for free, through airdrops or other delivery methods. We'd want to ensure that the majority of the smart phones reached real citizens, and not the regime. And our control of the network would mean that citizens could communicate with each other and the rest of the world without the regime intercepting, blocking, or listening to the messages. This would cost billions, but would be far cheaper than troops on the ground, and maybe more effective. It is also a beautiful asymmetric attack. If a repressive regime retaliated by building a free smart phone network for us, I think we would welcome it. Tell your congressman about this idea. We should give away smart phones and operate networks that cover the world's repressive regimes! But in the meantime, pray for the people of the countries that are rioting, and hope they get better governments than what they have now. I think the best action we as outsiders can take is to ensure that all of those involved are able to communicate with each other and the outside world. Comments |

Related: economics > geopolitics < predictions Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics science |

||||||||

| Wed Nov 4 22:47:02 2009 Yay! More torture. More notes on the economics of torture. |

|||||||||

| In May, I tried to make

the case for disallowing torture of suspects, even (gasp) terror suspects.

At the time, the torture memos were making the headlines, and as a result many people were asking if and when torture was ever appropriate. In fact, people started re-examining a number of moral issues in combat against terrorism. Here are some of the better articles I ran across. First, this article from Slate documents the current legality of assassination. This is from Slate's "Explainer" series, which is fascinating but purposely sticks to the facts. That's fine: the whole point of this article is to call out the supposed legality (or not) of political assassinations. Certainly President Ford's 1976 Executive Order banning assassination is the starting point. (By the way, that's a surprisingly readable document!) The point of the Slate explainer article was that although killing heads of state is clearly off-limits, targeting terrorists or "part time" combatants is much more problematic. Curiously, the Slate explainer article doesn't say so explicitly, but killing suspected al-Qaida members in CIA-sponsored Predator attacks would also seem to be illegal. Now that the CIA has terminated its al-Qaida assassination authorization, perhaps the US and other intelligence agencies will capture or disrupt terrorist organizations without killing suspects? A harder mission, but keeping the high moral ground is much more honorable and probably more effective. Why do I say that? Well, for one thing, there is a chance that torture makes the FBI's job harder, because the agency will have a harder time cultivating double agents. The argument is that engaging in torture "casts doubts on the U.S. government's overall willingness to act in good faith." I'm guessing most terrorists are irrational, and won't care whether we torture or not. But many of these potential double-agents are fairly rational people ("diplomats, scientists, or scholars"), not terrorists, and so the high moral ground may actually make a difference in the FBI's ability to turn foreign agents. Most interesting of all was an article by a former legal advisor to the Israeli Defense Forces, who had made frontline decisions about "targeted kills." That's kind of an euphemism for assassination, but the author believed there was a distinction between political assassination (targeted kills by nonmilitary, nonuniformed agents) and targeted kills made by uniformed military personnel in a combat zone. The author advised Israeli military commanders (in the field) from 1994 to 1997. To my civilian mind, the author's viewpoint was somewhat brutal. As he ends his article: ... if you're sure you've got the right guy, and you have no other viable options, fire away. The nation's safety may depend on it. This reminded me of situations the Slate explainer called "[adopting] a classic aspect of law-enforcement philosophy to justify an otherwise blatantly criminal action." But this really all comes down to whether or not self defense is justified. And that is an especially hard problem in combat zones. But for all of his at-times hawkish tones, the Israeli military advisor was pretty harsh about the US Administration's authorization of al-Qaida assassinations. As the author put it: Counterterrorism, in civil democratic regimes, must be rooted in the rule of law, morality in armed conflict, and an analysis of policy effectiveness. There can be no "ifs, ands, or buts." Even a hawk on the front lines of an anti-terrorist war takes a hard line on law and morality! But after all, that is a good deal of what he is fighting for. I think whether or not the nation supports assassination or torture depends on the current emotional state. If there is another terrorist attack, the majority will certainly accept (if not demand) targeted killings of suspects without trial--at least for a while. But the current less-passionate debate, from a number of sources, would indicate that torture and assassination--any methods of dubious morality--are probably self-destructive in the long run. Comments |

Related: economics > geopolitics < Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics predictions science |

||||||||

| Wed May 6 22:41:32 2009 Is Torture Worth It? The Economics of Collateral Damage |

|||||||||

| Lately, the

torture memos have been making news (and see more information about the memos at

the ACLU's website).

The left claims that torture is immoral, the right claims that Bush kept us safe. I have no intention or desire to write a political blog, so I'll stay out of that. But a state's decision to use torture has economic (game theoretical) implications, and it's worth considering those. And it's more than just torture: how far do you go to respect human rights? For instance, we have killed a lot of civilians in the Iraq war alone, and just today we apologized to Afghanistan for killing so many of their citizens in airstrikes. Here is one thought experiment: suppose a large terrorist faction hides people and material in a large United States city. The government discovers that the faction exists in the city, but doesn't know exactly where. Is it okay if the government bombs city blocks it suspects may contain terrorists, but isn't sure, even if there are a lot of innocent US civilians also there? I don't think the government would do such a thing. I'm guessing risking US civilian lives would not be an option at all. However, a different standard clearly applies for non-US citizens. We bombed large sections of Baghdad, killing hundreds of civilians, based only on rumors of Saddam Hussein's whereabouts. (In the end, all those civilian deaths were in vain, since Saddam was captured without a shot in Tikrit). And we continue to shell Afghan villages with less safety checks than we would use for US towns. Game-Theoretical reasons the US should not respect human rights:

Most of the above reasons are only valid in the short run. If an "abandon all human rights" policy prolongs or intensifies the conflict, then any short-term savings in lives or money are likely to be swamped by the costs (in money and lives) of a longer or more intense conflict. And #4 (would-be terrorists will think twice) assumes that terrorists are rational, and they almost always aren't. I don't think a strategy will get very far if it assumes terrorists are rational. A better (and probably safer) strategy is to assume that terrorists aren't rational, except in a twisted way that they want to inflict as much damage as possible. For those sorts of worst-case terrorists, #4 (promising them punishment) won't help. Instead, the approaches should focus on the people who are rational. These are typically the civilian populations that house, feed, and supply terrorists, and the politicians in those areas. The civilians involved are either coerced or sincerely believe they are doing the right thing by helping the terrorists. Politicians as a whole are shrewd calculators and strategies that open up political advantages to cracking down on or disavowing terrorism will likely yield results. Game-Theoretical reasons the US should respect human rights:

For these sorts of asymmetric conflicts, claiming the moral ground may actually be a key to winning. Our short-term costs, in terms of money and time, may be higher (and we may have to spend more money to protect lives!) but over the long run, this is the approach that will win allies and even the terrorists' host populations. Any strategy that antagonizes the host populations runs the risk of prolonging the conflict, and any strategy that antagonizes the host populations and our allies is almost certainly doomed to failure in the long run. So based on what I hope is a relatively dispassionate consideration, respecting human rights is the best long-term way to win the conflict. And by "respecting human rights," I'd recommend treating every civilian on the planet as if they were a US citizen, at least when considering military options. It makes military operations much more complex and expensive to plan, but has the best chance of keeping the conflict short and winning many allies. This argument does assume one thing: that there is a moral high ground. If all morals are relative, then none of this applies and we're back to a most-aggressive-combatant-wins strategy. And in that case, "terrorist" is also a relative term. So I'll stick with my assumption that there is a moral high ground. Comments |

Related: economics > geopolitics < Unrelated: books energy environment lists mathematics predictions science |

||||||||

| Links: |  |

Blog Directory | Blog Blog | Technorati Profile | Strange Attractor |