|

|

2001 February Trip - Tunisia

Six days in Tunisia.

Arriving in Tunis (10 Feb)

The Tunis Medina (11 Feb)

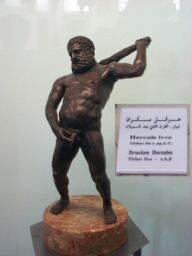

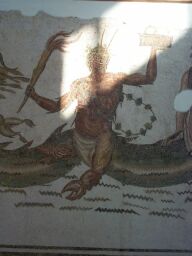

The Bardo Museum (11 Feb)

Dinner (and Running the Tout Gauntlet - 11 Feb)

Exploring Tunis (12 Feb)

Sidi Bou Said (12 Feb)

Carthage (12 Feb)

The Drive to Teboursouk (12 Feb)

The Ruins at Dugga (13 Feb)

Driving to Le Kef (13 Feb)

Le Kef (13 Feb)

Jugurtha's Table (14 Feb)

Driving to Sbeitla (14 Feb)

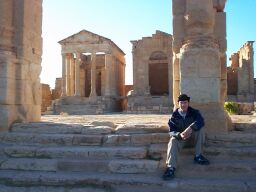

The Ruins at Sbeitla (Sufetula - 14 Feb)

Driving to Sfax (14 Feb)

A Day in Sfax (15 Feb)

The Colisseum at El Jem, and Tunis (16 Feb)

Comments

Arriving in Tunis (10 Feb)

The flight was somewhat long (indirect, with a long layover in Rome), but

otherwise pleasant. Alitalia flights always feature an Italian version of

Candid Camera that make me laugh in spite of myself.

I arrived at the Tunis airport around 9 o'clock in the evening. It was a quick

walk through customs, and then into the main terminal. I needed to get some

local currency.

A smartly-dressed man was standing around, watching new arrivals.

"Taxi?" he asked me. I did need a taxi, but I needed cash first.

"Is there an ATM around here?" It didn't register.

"Distributeur de billets?" I asked again.

"Ah, oui," he replied, pointing me down the terminal. He followed me at a

distance while I withdrew some cash. Then it was my turn to follow him, this

time to his taxi.

"Hotel Carlton," I said.

"Oui."

He didn't have a yellow-colored taxi, like everyone else. He had a beaten-up

old white Mercedes-Benz, with a removable Taxi sign on the top. He took it off

and put it in the trunk. There was a long taxi queue, and other taxi drivers

shot him nasty looks as he had obviously poached a fare by running into the

airport. One of them approached, and spoke quickly. My taxi driver shrugged

his shoulders, and replied back, then asked me: "Your hotel?".

"Hotel Carlton," I replied. This seemed to satisfy the other driver. All I can

guess is that my driver justified queue-jumping by claiming some sort of

affiliation with the hotel.

Anyway, it was a bit unusual. We pulled away.

Leaving the airport, a white van drove up next to us, honked, and then pulled

off to the side of the road in front of us. We pulled over and stopped behind

it.

"My father," explained my driver.

Sure enough, an elderly Tunisian man stepped out of the van and walked back

towards us with a wide grin on his face. It appeared to be the driver's father.

They spoke rapidly, I think in Arabic, if it was French I didn't catch a single

word. After a minute, a woman who I assume was his mother stepped out of the

van and joined the father, standing by the driver door of the cab, talking to my

driver. At one point the driver gestured at me. The parents waved.

"Bonjour," I said, and waved back. What could I do but laugh?

After a minute of more (to me) unintelligible conversation, the father punched

his son pretty hard on the shoulder, they both laughed, and the mother and

father got back into the van. We drove off again.

On the way to the hotel, the driver and I fired brief snippets of conversation

at each other. My French and his English were about the same, so we would ask

and reply in either language.

Once again, I was entering the city while it was dark, and so it was hard to get

a feel for how the place really looked. The road from the airport skirted Lake

Tunis on one side, and high-rises on the other.

Entering central Tunis was interesting. It had a far different character than

Istanbul. There were a number of abandoned buildings. Architecture was

predominantly very ugly 1960's style concrete buildings, with chunky, awkward

balconies and crumbling facades. A lot of sidewalks and streets were in

disrepair. There were a number of guards, stationed seemingly at random, with

intimidating automatic rifles (although I've never met an automatic rifle that

made me feel warm and fuzzy).

We finally pulled onto Avenue Habib Bourguiba, which looked like a war zone. A

construction crew was ripping up the road, meaning there were piles of dirt and

temporary barriers everywhere. A man threw up violently on the sidewalk as we

slowed near the hotel.

"Il a bu," chuckled the driver.

We pulled up in front of the Hotel Carlton. There were large holes in the

sidewalk, where the paving stones had broken or simply disappeared. There was

very little trash, but a lot of dirt. I pulled my bags out, and asked the

driver how much I owed him.

"Cinq dinars," he said, or at least I'm pretty sure that's what he said. That

was the guidebook's estimate for a fare from the airport. I gave him a ten,

since that was all I had. He shook his head. We exchanged a few words, but

were unable to communicate. I was under the impression he couldn't make change.

He followed me into the hotel.

The reception area was pleasant, although not as nice as the Blue House in

Istanbul. There was a young man behind the counter. He and the driver spoke

briefly. The driver changed the ten for two fives. Then he held out his hand

again.

"Dix dinars."

"I already gave you ten."

"Quinze. Fifteen."

"What? Five."

"No, fifteen."

"It is fifteen," said the receptionist. "It's a larger taxi."

Larger taxi? Maybe if you measured in centimeters. Both men looked slightly

insulted, but I couldn't tell if they really believed that fifteen was a

reasonable fare, or if they just thought it was natural for foreigners to pay

extortionate taxi fares. But it was late (at least for my internal clock), and

I didn't think it was worth arguing any further. I handed over another ten and

received a five in return. The taxi driver left, and I checked in. The Hotel

Carlton was far less than half the Blue House's published rate, and a good deal

less than what I had actually paid. I followed a bored-looking Tunisian bellhop

to my room.

The room was a disappointment. The hotel was listed in the guidebook as a top-

end hotel, and supposedly rated three stars. The twin beds and bedspreads

looked older than I was, as did the furniture. The tile floor was clean, but

heavily scuffed and scraped. The view out the window was a dark, forbidding

alleyway of cement buildings.

I unpacked and went to bed feeling slightly uneasy. Had the taxi driver and

receptionist worked in collusion to cheat me? If so, how much did I really

trust the staff here? Would it be safe to leave my laptop in the room (even

buried in my packpack) while I was out for the day?

The Tunis Medina (11 Feb)

I slept like a log, and woke up feeling much better. The furniture was old, but

functional and comfortable. The view out of the window was far less forbidding.

And the hotel breakfast, while again not as nice as the Blue House, was filling

and served in a large, airy room filled with morning light.

Best of all, there were many other tourists here. Knowing that there were other

people in my situation calmed me even more. I decided not to switch hotels.

Pretty much all of my clothes, except for what I was wearing, were dirty. So I

handed them over to the hotel for cleaning.

I walked down the Avenue Habib Bourguiba. A man asked if I wanted a shoeshine,

and I declined. I was wearing my cross-trainers anyway.

Another man walking near me laughed, and pointed to his own shoes. He was

wearing tennis shoes as well.

"Not much use for a shoeshine, eh?" he said with a smile.

"Where are you from?" he asked as we walked. We talked for a bit, he was

heading to the medina as well.

"Today is special exhibition."

"Oh really?" That was good luck. Everything in town was closed, it sounded

like the medina at least would have something going on.

"Yes, a Berber handicrafts fair."

"Sounds good." Not as interesting as, say, sword swallowers or a cheerleading

exhibition, but at least it was something.

"Many things. Carpets, kilims, jewelry."

"Ah." For the first time, I got suspicious.

"But we must hurry. Closes very soon."

I almost stopped. This was *exactly* the same pitch that had pulled Paul

Theroux into a carpet shop in his book "The Pillars of Hercules." I mean,

didn't these people know that particular ruse had been exposed years ago?

I refused to follow the man, obviously a carpet tout, into the medina. When he

realized I was going to go my own way, he left for other prey.

I stood at Bab Bhar, the massive gate leading into the Tunis medina. The

gatehouse stood on its own, years ago the nearby medina walls had been ripped

down so some streets could be built, fortunately that wasn't done often and most

of the medina walls are still standing.

The touts in the medina were far more agressive than in Istanbul. I was glad I

hadn't visited Tunis first. I had several people walk up to me with various

phony introductions. I made the mistake of telling one where I was staying,

which was useless information to him but another tout (who must have been nearby

but invisible) later introduced himself as working at the hotel. Another man

tried to get me to visit a nearby terrace for "panoramic views" (Theroux also

encountered this one: to get to the terrace you have to go through a shop). He

combined the two tactics: it was a great view, *and* it was closing soon. His

claim to legitimacy was that he supposedly worked at the mosque I was visiting.

He spoke only in French, although he knew one or two words of English.

"C'est gratuis, non? No charge!"

"Non, merci."

"You have no confidence in me? You think there are no gentlemen in Tunisia?"

he asked in French.

"Je ne vous comprend pas," I replied. Sometimes ignorance is the best

diplomacy.

The touts seemed more desperate here, compared to Istanbul. They were rarely

rude, but they usually made it obvious that they felt you'd insulted them if you

didn't fall prety to their pitch. And I suppose that after the tenth or

twentieth person walked up to me and said: "Where you from? America?" I started

to become less and less civil myself. It starts to erode your faith and trust

in other people. Actually, by around 11 I wouldn't have trusted my own mother.

I walked through the medina. Tight streets weaved through a maze of cracked

walls and beautiful doorways. Once in a while a young Tunisian on a motorbike

would zip by at insane speeds. Cars were much rarer, and much slower, since

they had to be careful about scraping the walls on either side (and from the

looks of both cars and walls, many drivers weren't careful enough). I spent

several hours walking, trying to follow the guidebook's suggested walking tour

but getting lost quite often, detours which were often as interesting as the

official walk anyway.

The medina's "attractions" (mosques, mausoleums, museums, shops) weren't

terribly exciting to me, certainly nothing compared to the Aya Sofya or Kopali

Sarayi. The main attraction was the architecture of the medina itself. If you

ignored the desparate touts and the shops full of tourist junk, you could start

to sense what it must have been like, living here where nothing changed from the

fall of Rome to the invasion of Europeans. Off the main tourist souks, you

would find real Tunisians engaged in real commerce or even relaxation. I felt

notably less welcome here than in Istanbul, although nothing close to

resentment. I suppose that's natural, given that the per-capita GDP and

standard of living is lower in Tunisia.

After several hours, I stopped in one of the cafes. It was in the Turkish

section, and was supposedly an authentic Turkish cafe. Instead of seats, there

were woven reed mats placed on top of large stone benches. The patrons would

sit with their backs against the walls, feet straight out in front of them on

the bench. Everyone smoked like it was required. Blue smoke wafted towards

the high, arched ceiling. I had a thick, sweet Turkish coffee and wrote some

postcards.

After that, I wandered back towards the hotel. Many shops were still closed,

but Tunis was far more alive now. More people were on the streets, more cars

were driving around. I grabbed some lunch, and decided to visit the Bardo

Museum.

The Bardo Museum (11 Feb)

On arrival, I paid the entrance fee (including the universal 1 dinar surcharge

for taking pictures). There are two reasons for going to the Bardo: the

mosaics, and the building itself. Or so said the guidebook, and I agreed.

I'm not really much of a museum person. But I enjoy architecture, and this

introduction to mosaics was a novelty for me. I'm not competent to judge the

artistic or technical merits of mosaics, but there were many of them, and they

never ceased to amaze me. The same can be said for exploring the building.

At one point, I ventured down a short stairwell to view a small balcony with

mosaics. The balcony was closed for repairs. As I turned to leave, however, a

guard ran up to me.

"I let you in."

I wasn't sure what he meant. But he started to unlock the large padlock. Just

then a large group came through, the tour guide talking in rapid French. The

guide motioned for me to wait. We stood there until the group left. Then he

unlocked the padlock, and opened the small gate. I walked around some

scaffolding, and looked down.

We were in a room I'd visited before. It had two balconies, both of which were

closed. It was nice to have access to this particular vantage point. The

ceiling was beautifully textured and painted. I took some pictures of the room.

"Mosaic," said the guard, pointing at the wall. There was a good-sized mosaic

there, but it didn't strike me as noticeably better than any other mosaics in

the museum. But the guard was very persistent, so I obligingly took a few

pictures.

Afterwards, he locked up the balcony again, and motioned for some sort of

payment. I asked him how much. "Ten dinars," he said with a shrug. Yeah. I

gave him three dinars (around three dollars) and pretended I didn't have any

more. He seemed satisfied.

I thanked him and started walking away. He asked: "Sir, do you have pen?"

I did, and offered him two. I thought he needed to write something down. He

chose one (the nicer one), pocketed it, and said thank you. Apparently it was

part of the payment.

I noticed many guards being especially helpful towards museum guests, and I

assume that none of it was free. By Western standards, it's annoyingly corrupt.

But I'm sure the pay for these jobs is very low, and these men need some way of

supplementing their income.

But I brushed off the guards after that.

On the tram back to the center of town, I fell into conversation with a Ghanan

with the improbable (first) name of "Smith." He'd been working in Tunisia for 6

months, and didn't enjoy it much. Although his French was far better than mine

(Ghanians speak English, so French was a second language for him as well), he

still found it hard to communicate.

We talked on the tram, and he said if I was in town tomorrow, he had the day off

and would like to accompany me in sightseeing. This is just the sort of

proposal I'd been programmed to decline, but I felt inclined to trust Smith. So

I agreed, although the next day (Monday) already had the makings of a very busy

day. A part of me worried that he'd end up being another tout with something to

hawk.

Once back from the Bardo, I rested at the hotel for a while. Then it was off to

a restaurant. By this time, it was dark.

Dinner (and Running the Tout Gauntlet - 11 Feb)

When you go to look for a restaurant in an unfamiliar city with suspicious (or

aggressively intrusive) inhabitants, what you most desire is that you spend a

lot of time walking down dark streets, looking lost as you fumble with a map.

Fortunately, Tunis makes that easy. Following the European model, streets are

inconsistently and sporadically labelled. I made many wrong turns before

finding my address, even though I was only going a few blocks. And then the

first restaurant I had chosen was closed ("tout les dimanches" il a dit). The

second restaurant was in a hotel that was completely shuttered. This gave me

plenty of opportunities to get lost in the dark alleyways off of Avenue Habib

Bourgiba.

In the short three-block walk to the first restaurant, I was accosted three

times. Always a friendly gentleman that wants to know the time, oh you're

American, let's have a drink...

The "let's have a drink" scenario can have far less happy endings than just

ending up in a carpet shop. I'd been subjected to these approaches in Istanbul,

but they seemed more sinister here (and they were definitely more numerous).

Of all the outstanding problems in Engineering still facing mankind, the one

that comes to my mind most often is that of avoiding touts and other similar

undesirables.

In Istanbul, polite but firm denials were sufficient. Here, the persistence of

touts makes such an approach tedious, and the sheer density means that by the

time you have rebuffed one, two more are waiting in line.

I could just be very rude right away. That does run the risk of insulting

genuinely friendly people (however rare they may be). Even worse, being rude

may provoke much more negative responses from the tout that are better avoided.

And in any case, I don't want to provide them with any justifiable sense of

moral indignation.

Rather than an active repellant, some sort of passive defensive system is called

for. I'm reminded of the urban legend of the man who puts a sign saying

"Caution: contaminated infectious blood transfer vehicle" on his car so it never

gets towed or ticketed, no matter where he parks.

Perhaps that would do it? Wrap some "biohazard" tape around myself to scare

people away? Wear a glowing green radiation symbol? A "Pat Buchanan for

President" button?

I've also thought of reverse psychology.

"Are you American?"

"Yes, I'm flattered and impressed that you figured that out."

"Would you like to see some carpets?"

"Yes, I would *love* to see some carpets. I'd go anywhere with you. Would you

have a drink with me too? Will we make it before your store closes?"

The problem, of course, is that if they call your bluff then you've really

screwed yourself. And if you go too far over the top, you become rude, and

we've already dismissed that as an option.

I can't pretend that I don't speak English or French, because the only language

I could pretend to know instead would be German, and many of the touts here are

bound to know some German.

I could also tout them right back.

"You American?"

"Yes."

"You visit Tunisia?"

"No, I work here. I've got a small shop. This way, hurry, closes soon. I give

you special price."

"No, you don't--"

"No, no," as I pull at their sleeve, "you like. Come with me."

I had dinner at the Restaurant Baghdad, which feels very un-American but damn

it, I was running out of options. By some coincidence, after all of my

wandering around in the dark streets, the restaurant was the next door up from

my hotel.

The food, like everywhere else on the trip so far, was anti-vegetarian. The

waiter managed to find something I could eat.

A band played vaguely electro-Persian music. As far as music you can eat to

goes, it was pretty good. Judging by an older woman sitting by the keyboard

player, heckling is an international profession. Well, that's why you're in a

band anyway: to meet women.

I asked for coffee with dessert three times. It wasn't until the third time that

I realized that he was saying that coffee came with the dessert. Stupid

American. The coffee was more of that thick, sweet Turkish coffee that I've

come to enjoy.

Every two minutes, someone's cell phone went off. Some things you just can't

escape (unless you head off into the wilderness, which is too much like work to

count as a vacation).

I walked the five steps back into my hotel, and crashed for the night.

Exploring Tunis (12 Feb)

In the morning I had breakfast, then met Smith as planned. I had only an hour

or so before I had to check out. Smith took me back into the suburbs of Tunis.

We walked by the church he attends, apparently the only English church in

Tunisia. Only around 40 people attend services, including the French and

American ambassadors.

Then we walked back through the markets. Not the tourist stalls in the medina,

but the places where real Tunisians shopped. Nestled at the base of the narrow

canyons of the Ville Nouvelle, there were rows of used clothes, purses, shoes.

There were streets lined with stalls selling fruits, vegetables, fish, chicken,

beef. I didn't see a single tourist.

Smith kept laughing at me. To him this was terribly mundane, as if a friend

came into town to sightsee and I took them grocery shopping.

But that was exactly why I enjoyed it. After the surreal experience of Avenue

Habib Bourgiba with its seedy touts, these suburban markets grounded the city

in reality. Even better, not a single person pestered us (at least, not once we

were away from Avenue Habib Bourgiba).

After that, we walked back to my hotel. I checked out, and had them hold my

bags while I went out to look for a rental car. Smith came with me--he said he

had the day off anyway. I suspect that he had few occasions to meet other

foreigners, and he was in a position (staying in the country only for a short

while) where it was difficult to meet peers. I knew how he felt.

The rental office was a tiny, smoky room in a street off of Avenue Habib

Bourgiba. The French family in front of me was arguing back and forth about

renting a car for the day, worrying about breakdowns and needing assurances on

many points that my French was inadequate to discern.

When it was my turn, my choices were simple because they only had one car left:

a Peugot Saxo, which I'd never heard of or seen before. I quickly rented it (I

didn't even try to haggle, but the rate was below what the guidebook had quoted)

and Smith and I drove off, back to the hotel. We collected my bags again, and

headed off for Carthage.

I knew that driving in Tunis would be challenging, and I was not disappointed.

Pedestrians walked in front of us. Young Tunisians on motorbikes would quite

often head obliviously against the flow of traffic. Impatient taxi drivers

would honk at you if you didn't move quickly enough, or if you left too much

room between you and the car in front. If you were at the front of the line,

waiting at a stoplight, it was expected that you slowly inch into the cross

traffic, until you were halfway across the road when the light turned green.

Drivers behind you would honk to let you know when the light turned green

(because by this time, it was behind you and you couldn't see it), so you could

move forward and cross the last half of the intersection.

On the other hand, at least the driving was on the right hand side of the road.

I'd have been in real trouble if in addition to the traffic hazards, I had to

deal with a stick shift with my left hand, and sit on the right side of the car.

I started to see why people tended to drift, keeping their cars in two lanes at

once. You could never tell from which side a pedestrian or motorbike or anxious

taxi driver might materialize. Driving in the center (straddling the lane

markings) seemed safer. Taxi drivers also liked having the option of moving

into either lane as openings in traffic appeared.

Fortunately (and with only a few unintended detours) we quickly made our way out

of the city, and the traffic thinned out. I was able to drive faster again, and

any doubts I had about renting a car melted away. Instead of dirty and decaying

buildings, we passed long rows of tall trees, shepherds with flocks of sheep

(often grazing beneath powerlines, between vacant and abandoned building lots).

The tachometer confused me greatly, until I realized it was a clock.

Sidi Bou Said (12 Feb)

I had decided to visit Sidi Bou Said first, and then Carthage if there was time.

The guidebook mentioned that so little remained of Carthage that there just

wasn't much to see. Sidi Bou Said, however, was mentioned prominently as a

must-see attraction (and indeed, the cover of my guidebook featured a doorway

from there).

Sidi Bou Said is a small community of whitewashed houses, and the only other

allowed colors are black (for trim only) and sky blue (for windows and doors).

The result is a very consistent and distinctive look, much like a Greek village

(as the guidebook said). Only you would bump into mosques instead of churches.

We walked through the few square blocks, admiring the houses. Many of them were

beautiful summer homes, I'm guessing for either very rich Tunisians or

foreigners. Though open doors and windows we would get hints of the rustic (and

very stylish) interiors. Expensive cars were safely stowed behind large gates

and whitewashed walls.

We came to a promintory, overlooking the Mediterranean. It was the first time

on my trip that I'd actually seen the Mediterranean. The waters were a bluish-

green, with bits of white on the waves, whipped up by a fairly strong Eastern

breeze.

We found a small cafe and sat in the sun (and quickly moved to the shade--it was

a hot day). The single waiter seemed overwhelmed, so we left without being

served. But the point was just to relax and enjoy the view anyway.

I found the door featured on my guidebook (and also on many postcards). I of

course had to take a picture of it.

We walked down out of Sidi Bou Said just after two o'clock. I decided that we

had enough time to take a quick look at the ruins of Carthage, so off we went.

Carthage (12 Feb)

It took us some time to find the National Museum, but find it we did. It was on

a large hill (Byrsa Hill), overlooking the city. A Roman Catholic church stood

on the top. Next to the church was the museum, featuring the ruins of Carthage.

I read a book on Hannibal over the summer, and so was eager to see the ruins.

As I remember, Hannibal himself was raised in the Carthaginian colonies in

Spain, led an army across Spain, the Pyrrennes, and (of course) the Alps, and

terrorized Italy (then under the control of a Roman Republic) for seven years.

But the Romans seized control of the sea while Hannibal wandered Italy, and

threatened to invade Carthage. Hannibal was recalled to defend his homeland,

and I believe that the first time he ever saw his home city was on the eve of

battle. He was hopelessly outnumbered, for Roman manipulation of his North

African allies and a few twists of fate conspired against him, and the battle

was lost. He fled and eventually committed suicide to avoid capture.

Later, in the second Punic war, Carthage was completely sacked and then razed by

Rome. Hence all that remains are a few bits of columns. In fact, I think the

museum curators realized that they were faced with a shortage of real ruins,

and so as we walked through the grounds we were constantly presented with

detailed maps and renderings of historic Carthage, as if these would make up for

the lack of anything more tangible. But the price of admission was worth it,

just to stand on the ground.

There was an indoor section of the museum, housing relics and mosaics (although

many of the most beautiful mosaics had been carted off to the Bardo). After a

day of walking, my tolerance for museums was pretty low, and I started to fall

asleep on my feet. So we walked quickly through, stopping only occasionally,

and eventually left the grounds.

One of the most memorable parts of the museum was a large map of the Roman roads

in Tunisia. I couldn't help but notice that the modern highway system looked

identical--the highways were built on top of the Roman roads.

I dropped Smith off at the tram station in Carthage. I didn't want to drive

back into Tunis, and in any case it was getting late and I wanted to arrive in

Tebourksouk (the town with a hotel near Dugga, my next stop) before it was dark.

We shook hands and exchanged addresses. I had been considering heading off to

Dugga earlier in the day, and catching Carthage only briefly on my return to

Tunis days later. Spending the day with Smith was much better: he had shown me

a more human side to Tunis in the more common suburbs, and had saved me time by

knowing the way around the streets of Tunis and Sidi Bou Said.

The Drive to Teboursouk (12 Feb)

So I drove off to Teboursouk. The outskirts of Tunis were fairly crowded. I

had to overtake beat-up old cars that were barely moving, and get out of the way

of impatient BMWs and Mercedes. Two cars ahead of me, the hood of a dilapitated

Fiat popped open at around 30 mph, luckily the driver made it to the side of the

road without killing anyone (or getting killed himself). Behind me, riding my

bumper, was a battered truck with a large wooden boat roped on top.

Once I was well away from Tunis, and into the countryside, the ride was very

pleasant. The hillsides were covered with small, dry, leafy trees in neat rows,

and the fields were freshly cut. I passed many flocks of sheep with shepherds

eyeing me warily. In the smaller towns, I passed people riding donkeys,

pulling carts piled high with foodstuffs.

One weird aspect of Tunisia is that even in the small country towns, everyone

dresses as if they were in downtown Tunis. Fashions are very consistent. I

suppose that's not a huge surprise: even given wide disparity in incomes, the

per-capita GDP of Tunisia is well over $2000 (US). Tunisia is a third-world

country in political terms (never closely aligned with the Soviet Union or the

US), but it doesn't fit the poor stereotype of what people normally refer to as

a "third world country."

But the unemployment rate is a real problem. Smith quoted me a figure of 60%,

the guidebook (a few years out-of-date, I'm sure) quotes something more like

20%. I'm guessing the real value is in-between. But it means that many young

Tunisians have no jobs, and nothing to do but loiter. Hence the number (and

persistence) of the touts here.

I don't know the answer to the problem, which is rooted in the somewhat closed

and overly bureaucratic political system. Just before my trip, I read Kissinger's

"Years of Upheaval," the second volume of his memoirs. He mentions the same

problem which he saw in other countries. How does a country, steeped in its own

culture of (typically) autocratic and rigid hierarchical social bonds,

disentangle the political from the cultural? Kissinger believed that Westerners

had a long cultural heritage of understanding the difference between country and

political party, between cultural identity and political causes. He stated that

such distinctions are rare, and that without them true democracy is impossible.

In most countries, the idea of the nation state is inseparable from the concept

of the ruling party, therefore opposition parties are typically viewed as anti-

nationalist. Hence the typical pattern of Western democracies supporting and

promoting democratic freedoms in developing countries, which typically led to

bloody internal conflict followed by regimes just as repressive as the ones they

replaced. This was Kissinger's (implicit) defense of supporting dictators when

necessary in the cause of national (or international) security.

I suppose there's some truth to that. But that's not the feeling I get, talking

to Tunisians. There are pictures of Ben Ali (the current president) everywhere,

I assume it's some kind of law. The expression on his face is difficult to pin

down. I think he was aiming for a look that said "I have the vision to lead

you" but to my eyes it looks like he's saying "I can get the chicks." The

rulers of countries have a range of pick-up lines that aren't available to mere

mortals. But in any case, most Tunisians don't have a god-like respect for

their political leadership. Cynicism is probably a better word.

Sorry for the tangent. The undeniable fact is that Tunisia's unemployment rate

is very high by any standard, and so there are a lot of young Tunisians

loitering on the streets.

"They have no jobs, so all they do is sit in the cafes and drink and smoke,"

Smith observed as we walked through the suburbs of Tunisia. Smith, by the way,

was one of the very few people I'd met who didn't smoke. The absence of blue

smoke (or a hacking cough) was welcome.

"Sitting and smoking is better than rebelling," I replied. Smith laughed and nodded.

That and more went through my mind as I drove. The car didn't have a radio, so

I was left to my own entertainments. I would have conversations with invisible

friends, or practice the vocal calisthenics of a muezzin's call to prayer.

So I basically acted like I always do when I drive, radio or no.

It started getting dark. I had made a large detour to avoid Tunis, which in

retrospect probably wasn't worth it. Instead of being on the well-maintained

major highways, I was stuck with another hundred kilometers or so of secondary

roads, which were very unpredictable. At times they were wide and smoothly

paved, other times entire chunks were ripped out for maintenance (I hope), and

we few travellers would have to carefully steer our cars through potholes and

mud. Many of the cars on these back roads disdained the use of headlights,

often I was unaware of their presence until they beeped at me in annoyance,

approaching at high speed from the opposite direction, both of us hugging the

center of the road. I quickly got used to veering off to the shoulder at the

last minute.

Most of the major roads were well-marked, but occasionally an important sign was

left missing, or only indicated in Arabic. Again, this was a problem only on

the secondary roads. My trip lengthened as I spent as much as a half an hour at

some points, driving back and forth through a small, dusty Tunisian town in

search of a left turn that I knew had to be there somewhere.

I finally reached Teboursouk, the town outside of Dugga where I intended to stay

the night. The Hotel Dugga was my object, and I drove up and down the main

streets of Teboursouk in a fruitless attempt to find the place. My guidebook

listed no address or even a street, just saying it was "by the Tunis-Le Kef

road," which applied to most of the town. I spent the better part of an hour

looking for the hotel, becoming more and more frustrated.

In desperation, I decided to just call a taxi, and then follow it to the hotel.

I stopped at a place I'd passed many times, a "Taxiphone" station. The

guidebook mentioned these as being ubiquitous, and it was right. I saw them

everywhere. Now I really needed one.

I went inside. There was a bank of phones, and an attendant who was maybe 15

years old. I looked around on the walls. There were many numbers listed, but

the descriptions were all in Arabic. I asked the attendant: "Taxi?" He looked

at me blankly, or rather, with the expression "Why are you asking me?"

"Number for taxi?" I asked in halting French. Another blank look. "Number?"

He walked into the booth, and pointed at the number one. "One" He pointed at

the number two. "Two." You get the idea. All the way to nine and then zero.

Did he think I was so stupid that I couldn't read the numerals? I dismissed

that as ludicrous, rather I thought that some enterprising taxi company had

grabbed the phone number of 123-456-7890. So I dialed it. And, as you might

expect, I was greeted with a recording telling me I had dialed a ridiculously

incorrect number. I assume that's what the recording said, it was all in

Arabic. Sigh.

So I tried calling the hotel. I hadn't done this earlier, because I was

pretty sure that I wouldn't be able to handle complex street directions in

French. But again I was greeted with a recorded message in Arabic--the call

hadn't gone through. I groaned and went back to the attendant, who by now

was getting very tired of me.

I pointed to a number on the wall. "Taxi?"

"Hospital."

Another. "Taxi?"

"Police."

One more. "Taxi?"

"No," he didn't know the word for what it was, but it wasn't a taxi. I had

hoped that he would get tired of my pointing and asking and just point to the

number of a taxi company, but he didn't. He just kept looking at me as if

wondering how to get me back to the asylum.

"Look," I said. He followed me outside, where I pointed to the brightly lit

sign. "Taxiphone," I read.

"Yes."

"Taxi?"

"No." He looked at me like I had asked the stupidest question in the world.

I experienced a minor epiphany, one of those subtle realizations where you ask

yourself: "what else have I missed?" Of course, "Taxiphone" didn't mean that it

was a place to call taxis, it just meant you could hire a phone. The attendant

obviously didn't know the number to a taxi company, and the only phone books I

could find were in Arabic, I was wasting my time here.

It was getting late (after nine o'clock), it was pitch black outside of the few

street lights, and I was getting drowsy.

I went back to the guidebook. "By the main Tunis-Le Kef road." Did it mean the

hotel was *on* the Tunis-Le Kef road? I went back, out of town, to the highway,

and drove back a couple of kilometers towards Tunis. No luck. I turned around,

and tried the other direction. Bingo. Just past the Teboursouk turn-off, there

it was. Hotel Dugga was brightly lit, with a massive tacky replica of Ionic

columns in front. After all those missed turns, why had I found Teboursouk so

easily? If only I had missed that turn-off, I would have been in bed already.

With a curse for my technically correct but nonetheless misleading guidebook, I

pulled in and acquired a room. The hotel was all on its own on the highway, so

it had its own restaurant. I dined alone in a massive dining hall. There were

around thirty tables set up, and just I was there, served by three people. It

reminded me of "The Shining."

I stumbled back to my room. The room was freezing, lit by indirect blue

florescent lights that distorted all of the colors. The bed was old, and

somewhat lumpy. I slept for over ten hours.

The Ruins at Dugga (13 Feb)

I checked out of the Hotel Thugga in the morning. I drove up to the Roman ruins

at Dugga. I realized only when I was well on the way to Le Kef, after leaving

Dugga later, that I had taken the longest possible route to get to and from the

ruins.

It was a scenic drive. Here, away from the city, people (children especially)

would stop and stare as I went past. Old men and women in traditional Islamic

garb would shuffle along on the side of the road. Young men in Western clothes

rode on donkeys.

I assume the locals treated me with shock, laughter, and/or silent bemusement

(depending on the local) because I was a foreigner. It may just have been a bad

hair day.

On the map, it wasn't clear to me exactly where the ruins were. As I approached

it was obvious: tall stone columns were silhouetted against the morning sun.

I got there around 9:30. The guidebook recommended arriving as early as

possible to avoid the worst of the crowds. In my three hours there I saw only

two other couples.

As I got out of my car, a man stood from where he'd been reading his paper in

the sun. It was the classic tout aproach, but far less sinister this time. For

one thing, the guidebook had mentioned that it was common for guides to approach

you here, and they were usually worth it. For another, this was not a young man

casting furtive glances as he tried to hustle me. This was a middle-aged

gentleman who moved with a sense of ease.

Even so, there was haggling to be done. He quoted his prices, basically ten

dinars an hour, which was higher than the book quoted, and during low season I

expected the prices to be less. He quoted a rate for an hour, but said that an

hour and a half was a better tour.

"Hour and a half, fifteen dinar," he said.

"Ten."

"No." That was his final answer.

He started walking away. I started walking towards the ruins, debating with

myself. The ruins were huge, and my guidebook's narrative was (of necessity)

short. I needed a guide. I was about to call out to him and acquiesce, but he

called out first.

"Hour and a half, twelve dinars."

"Okay," I agreed.

Later, I felt guilty for even haggling. I haggled down the price by 3 dinars

for a pleasant guide who wasn't likely to have any other tourists that day,

while I hadn't even challenged the sleazy rental car agency? Life isn't fair...

Mohammed (as his name turned out to be) led me through the ruins. We walked

through the theater first.

"Actors here." Duh.

"Prompters here." Prompters? I didn't know they had--

"Audience. Three thousand five-hundred," he said, pointing at the stands.

"Rich up there," he indicated the seats at the top. "Poor here," the seats at

the bottom. So the Bill Gates of Dugga didn't have courtside seats. Human

nature hasn't changed, only the seat assignments.

Then it was on to the capitol building. By the capitol was a small court with a

compass for the winds. The hot desert winds, the cool sea winds. Today they

were cold.

Dugga was impressive. It's not a collection of buildings, it's a city. It's

the sort of experience that spoils you for future archeological exhibits.

Mohommed led me out of the city, through the western gate, where a temple stood

in the fields. Once a Punic temple, where they sacrificed small children, it

was later converted by the Romans for one of their gods (Caelestis), and the

sacrifices stopped.

It's no surprise that Christianity won the battle of religions around the

Mediterranean. "Join us or burn in Hell" versus "Join us and sacrifice your

children." The sheer horror of the Punic sacrifices was awesome (in the old

sense of the word). As far as psychic impact goes, it's hard to top sacrificing

your own children. It reminded me of the Mayan rulers' ritual of drawing blood

from their genitals. You just can't go any further than that.

The Mayans simply abandoned their cities when the rituals stopped working.

Again, it's not clear how to appease the gods if blood from your privates won't

do it. The Punic culture was taken over by the Romans, I suppose they would

have graduated to adult sacrifice otherwise.

After looking at the (formerly) Punic temple, we moved on back to the city.

There were two aspects of the ruins that seemed eerie. One was the roads. They

weren't terribly wide, but they were one of the most prominent artefacts still

visible. They wound from the Arch Alexander Severus to the Arch Septimus

Severus, and at points you could see ruts from the wheels of the chariots.

"Just like 520!" I exclaimed.

Mohammed ignored me.

The roads were eerie because they were such a connection with the past. The decay of

the buildings made it hard to picture people living or worshipping in them. But

roads are timeless.

The mosaics were the second aspect of the city that really hit me, much more so

than the roads. The stone walls of the houses were only partly standing, and

what few stones were standing had been heavily eroded. It was impossible to

really get a feel for how people lived by looking at them.

But the mosaics were still there. Many of the most impressive had already been

carted off to the Bardo in Tunis, and I'd seen them there. But there were still

some mosaics here from Roman times. In the corner of one small house, Mohammed

pointed out a small basin with a mosaic. He splashed some water on it, and the

colors brightened up immediately, as fresh as it looked 2500 years ago. The

sad, wise face of Neptune peered out at us, as fish swam around him. That was

when I started feeling like I was walking in someone's house, rather than a pile

of rocks. In other houses we saw bits of mosaics from atriums, bedrooms, dining

rooms.

We walked towards the main baths of the town.

"Good mosaics," said Mohammed.

I saw a well-preserved mosaic, and started to take a picture. Mohammed waved

his hands impatiently. This wasn't a good one.

We came to a better one. I started to take a picture. Mohammed waved me on.

This happened a few more times until we stepped down into the baths.

"Now," said Mohammed, "mosaic."

There were mosaics on all the floors. Some were huge. All of them were in

great condition. I suppose it's just a matter of time before they get carted

off to the Bardo. Sad, but if it has to be done to protect them then so be it.

Mohammed led me down through houses and temples to another set of baths. Here

there were passages beneath where fires were lit to heat the baths.

My hour and a half was almost up, and there was still more to be seen. Mohammed

made a catalog of the most important sites left to be seen: the brothel, the

Punic mausoleum, the Cyclops baths.

"I show you all for 15 dinar," he said. Only three more dinar, that suited me.

And in any case I didn't have the change for 12.

So we walked down to the brothel. On the way, we passed a smaller, emergency

back-up theater. A shepherd led some sheep through the ruins in front of us.

We came to a sign showing the direction to the brothel. A penis pointing at a

pair of breasts. No one ever accused the Romans of being subtle.

I was excited to take a look at the Punic mausoleum. Mohammed said it was built

in the 3rd century BC, well before the town (and he was right). What he tried

to tell me in broken English, and what I didn't realize until after reading my

guidebook much later, is that the English consulate removed the inscription

stone in 1842, and the entire tower collapsed. The English rebuilt the tower,

but kept the stone. Now you know where Jihads come from (not that Americans can

point any fingers).

At this point I said farewell to Mohammed. He was tired (his chain-smoking

probably didn't help), and he had seen some friends and/or family that he wanted

to get back to. For my part, I was ready to relax a bit.

After looking around the mausoleum, I wandered back towards the main entrance.

Mohammed suggested just walking straight back up towards the theater, but I

swung around in a wide arc so I could take a closer look at the Arch Septimus

Severus.

On the way, I caught a glimpse down an air shaft as I walked by a block of

ruined homes. It looked as if there was a large room down there. So I poked

around the ruins a bit, and found the entrance. There were several large

chambers within, some of them accessible only through small openings in the

walls of other chambers. I was surprised Mohammed hadn't taken me here--perhaps

he was claustrophobic.

From the Arch I walked back up, around the main hill, to the Temple of Saturn.

Again I saw openings to large underground chamber, but I saw no way in. The

only other visitor here was a bored donkey, grazing below the temple.

I walked back to the parking lot. A French couple was just leaving, and a

German couple had arrived a couple of minutes earlier. I got something to eat

(all they had was cookies and Coca-Cola, fortunately I had brought water with

me), wrote some postcards, ignored a bellicose cat nearby, enjoyed the view, and

then drove on to Le Kef.

Driving to Le Kef (13 Feb)

Driving doesn't usually warrant much of an entry in travel journals. I spent as

much time driving as I did looking at museums and ruins (probably), but it

doesn't get the same coverage. Mostly, of course, because it can be tedious to

recount. But driving was definitely one of the big pleasures of the trip. The

scenery was relentlessly beautiful, and changed in character from north to

south, east to west. On the open road, I was either treated to the pleasure of

a long flat stretch of road with nothing to stop me from pinning the spedometer

of my hardy Peugot, or hairy moments when I had to dodge potholes or inattentive

semi trucks. In the small dusty towns, I would slow down. Across Tunisia, it

was common for there to be intricately tiled sidewalks which were ignored.

There were pedestrians everywhere, and they would always walk on the street.

People would stop and watch me drive by.

I saw many people asking for a lift. I didn't stop--I never do in the States,

and after my experiences in Tunis I was worried that people viewed foreigners as

rich targets.

At one point, I was about to overtake a small van, but as I moved into the

opposite lane I saw that two policemen were in the road ahead. I slowed down

and got behind the van again. One of the policeman waved me to the side of the

road as we passed. I pulled over.

"Hello sir," he said (in French).

"Hello."

"Do you see the solid white line?" And indeed there was a solid white line down

the middle of the road.

"Yes."

"Where there is a solid white line, overtaking is forbidden." The word for

'overtake' was unknown to me, it sounded like he said 'oublie', or forget. But

his gestures made it clear.

"Ah, I see now. Sorry."

"No problem," he said, waving me on. "Welcome to Tunisia. Have a nice trip."

Le Kef (13 Feb)

And so I arrived in Le Kef. This time, I managed to arrive in the early

afternoon. Even so, getting to the hotel was tricky: Le Kef is a small town on

the slopes of a steep hill (topped by a kasbah), and it seemed all of the

streets were one way, pointing away from the hotel. But I finally found the one

street that fed uphill, and after threading my way through lounging young men

and loud schoolchildren, I pulled in front of the hotel.

After checking in (and snapping a few pictures from the rooftop terrace of the

hotel), I walked up to the kasbah. It was an old fortress, built in its current

form in the 16th and 17th centuries. As I approached the main gates, a young

man said hello to me.

"Entrance is free," he said.

"Okay," I said. I was a bit suspicious to his motives, but after giving me that

piece of information he walked away.

Indeed, entrance was free. Again, an older gentleman approached me and offered

to show me around. As in Dougga, my guidebook's description was short, so I

agreed. He didn't speak any English at all, but I was able to understand his

French most of the time. There is a lot of context in a fortress. When a guide

points to a room and says something, odds are he's describing what the room was

used for, and not digressing into a discussion of 18th century German philosophy

or horticulture.

He showed me around the stables, the prisons, the Bey's quarters, the main

court and the guard houses. The view from the top of the kasbah around the

surrounding countryside was spectacular.

The guide was most animated about the prisons. Apparently Habib Bourgiba and

many of his ministers were imprisoned here (for a few days) during the war for

independence with France.

After the tour (around a half an hour long, there wasn't a whole lot to see), I

paid him 5 dinars and thanked him. Then I wandered around the fortress some

more to take pictures. I saw the same young man as had spoken to me at the

gate. He was watching me out of the corner of his eye as he also walked around

the fortress. I ran into him again at the top of the tallest tower. There was

a small stone shack up there, and a tall metal tower covered in antennae.

"What did the man at the gate tell you?" he asked me in French. He didn't speak

any English. As with all conversations, there was usually an initial phase

where we sorted out what language to use. Usually the language was French. But

even when someone spoke to me in English, it was quite often so broken that I

would unconsciously reply in French anyway.

"What?"

"Did he charge you anything?"

"No." In fact, I hadn't been charged any entrance fee, and I had paid the guide

without his asking.

"But he showed you around?"

"Yes."

"You paid him for that?"

"Yes."

"How much?"

"Five dinars."

The young main looked incensed. "You should ask for it back. This is supposed

to be free. He stole your money."

I made some lame comment about asking for my money when I left. But I wasn't

going to make a scene for 5 dinars, especially when I had given it to the man on

my own initiative.

The whole time, of course, I was trying to discern the motives of this person.

What kind of scam could he be pulling? After Istanbul and Tunis, having

strangers walk up to me professing a concern for my welfare made me extremely

suspicious.

He asked me to stay and talk for a while, but I declined, saying I was hungry

and had to get something to eat. In fact, that was an understatement: I was

starving. I hadn't eaten since breakfast. But this also sounded suspiciously

like the "let's have a drink" lines.

I made a comment about the tower above us.

"Television, radio, and telecommunications." He motioned towards the shack.

"You want to see?"

"Sure."

He unlocked the shack. Here, in a stone shack on top of a deserted 17th century

fortress, racks and racks of high-tech electronics hummed quietly to themselves.

There was an array of power converters and switches for the telecommunications

antennae. The radio and television antennae had their own stacks of equipment.

Thick cables dominated the ceiling. There was a bank of batteries for the

telecommunication equipment in case the power was out.

He invited me to stay a bit more (I'm a geek, the gear was pretty cool) but I

declined. I said goodbye and walked around the fortress for a few more minutes

before leaving for something to eat.

I looked for a cafe, but there were only two I could find, overflowing with

young Tunisians smoking heavily. So I finally found a small store where I was

able to buy some food, and hiked back up to the hotel.

In retrospect, I should have taken food with me into the fortress. The young

man at the radio tower was just an engineer assigned to that station, probably

one of Tunisia's brighter and well-trained residents, bored out of his skull at

the top of a tower where very few people came by. Talking to him would have

been more interesting than walking through the rest of Le Kef, which I found

somewhat mundane. The view was great, the fortress was inspiring, but on the

whole I was ready to move on.

After walking around a bit more, I had dinner at a restaurant. It was run by

the same people as my hotel, although the restaurant was several blocks away.

Once again I had an omelet for dinner, which is embarrassing because a) it's

something I make myself for dinner quite often, and b) in spite of my omelet

expertise I could never make them this well myself.

The appetizer is common (so far) in Tunisia: green olives in a red sauce and

olive oil. The red sauce is exceedingly pleasant until it burns through your

sinuses.

I've had wine on a couple of occasions here. Each time, I've had to buy at

least a half-bottle (no such thing as wine by-the-glass). It's been the same

wine each time: red wine by the name of Magon, from Tebourba (I drove through

Tebourba in the dark). So far I haven't gotten myself embarrassingly drunk.

"Il a bu."

I had dinner at the restaurant, and afterwards I started walking back to the

hotel. On a whim, I changed course halfway and hiked back up to the kasbah. It

was closed for the evening, but I was able to scramble up some rocks to a point

high above the city, just below the kasbah's sheer walls. I could see every

light in the valley. I was hoping for a clear look at the stars, but there was

too much ambient light, so the view wasn't much better than from my house in

Seattle. I hiked back to the hotel.

Jugurtha's Table (14 Feb)

In the morning, I had breakfast and checked out. I wanted to make an early

start, and make a side trip to near the Algerian border. There, in the

mountains along the border, was a large flat mesa called Jugurtha's Table. To

get to it, I had to drive part of the way to Kassarine pass, and then take some

minor roads to a small village. From there you could walk up to the top.

Along the way, I stopped to pick up my first hitch-hiker. It was a little boy,

maybe 7 years old, hitchhiking to get to school. I figured I'd be able to

handle him if he tried to rob me or anything. He didn't speak any French, and

he would look at me with a kind of bewilderment whenever I wasn't looking at

him. He motioned and spoke excitedly in Arabic when we approached his school so

I knew to stop and let him out, a kilometer or so from where I'd picked him up.

I continued on to the small town of Kalaat es Sinan, still several kilometers

from the Table, although from here the mesa dominated the southern horizon. The

guidebook said that you were supposed to check in with the national guard here

before climbing, and check out again when you left. I drove up and down the

main street of the town, but couldn't see the national guard office (they were

usually quite easy to spot, with green and white signs in Arabic and French).

I finally pulled over at the most official-looking building I could find. It

was somewhat palatial, situated at the main crossroads. I think it was the

municipal headquarters or something.

Several older Tunisians were in the lobby, and they looked at me quizzically

when I walked in. One nearby asked if he could help me. I asked for the

National Guard office, and everyone looked very confused. It could easily be

that my French was incomprehensible. There were a few more minutes of awkward

conversation where I tried to explain that I was looking for the National Guard

office, and they tried to figure out what I was saying, asking me clarifying

questions in turn that I couldn't understand.

Finally I said I was going to Jugurtha's Table, and everyone laughed. They

couldn't understand why I needed to see the National Guard office for that. One

of them, and older gentleman, took me by the arm, and gestured that we go to my

car.

He climbed into the passenger seat, and directed me through the town. It's good

that he came with me, the crucial intersection wasn't marked. On top of that,

the street was used as a market. I didn't even know it was a street, but he

gestured me on impatiently, ahead into a throng of people. I slowly make my way

through the crowd, schoolchildren were walking around, people were shopping,

vendors were calling out. This was the main road to Ain Senan, the village near

the Table.

Once past the market, the man asked for pen and paper (I was nervous: this was

my last pen). He drew me a rough map of the village of Ain Senan, showing me

where to turn to get to the Table. I thanked him, and he climbed out (returning

my pen). With a wave, I continued on.

I finally reached the Table, and started walking around the sheer cliffs at the

base. It took me some time to find the stairway up to the top, the book's

description was somewhat vague ("Walk around the northern side, and once you

reach the eastern side the stairs will appear."). I regretted not bringing a

compass. After a while, the book's description took on biblical proportions:

"Walk ye to the east, and to the righteous the stairs shall appear." I started

to think I wasn't righteous.

But the stairs did appear, and I climbed them. It was eerie: for the entire

walk, I hadn't seen anybody, other than a few shepherds where I parked the car.

Perhaps this was a busy tourist attraction in the summer, but today it was

deserted.

Jugurtha was a Numidian king who had used this mesa as a base while he raided

the Romans around 100 BC. I had heard of the Numidians: it was their light

cavalry that Hannibal had used to devastating effect in his campaigns against

Rome (particularly his famous battle at Cannae) around 200 BC. The Romans had

defeated Hannibal at Carthage partly because they had convinced the Numidians to

switch sides. Now (100 BC) it seems the Numidians had switched sides again.

As I climbed up myself, I was easily convinced that the place was impregnable

to assault. The best you could do was besiege it, and hope the defenders gave

up in starvation. I did wonder how the Numidian king sheltered his cavalry:

there's no way you could get a horse up those steps.

At the top, I found (as promised) a small shrine. It was apparently deserted,

the gate was closed with twists of wire. I untwisted them, and walked in. The

inside was far less pretty than the outside, and in fact it looked as if it was

being used as someone's home. So I left.

I was surprised to come across a number of ponies. I counted five in all,

eyeing me with a combination of suspicion and hope. There wasn't much grazing

up here, I could see their ribs showing through their hides. Were they led up

the stairs? Were they carried when they were young? I couldn't figure it out.

Further along the top of the table, I saw a small flock of sheep (but no

shepherd was visible). Sheep were dumb enough (and to be fair, small enough)

that I could imagine them getting up and down the stairs--but barely. It'd be

a lot of work for the shepherd, I don't know why he'd bother.

I walked up to the highest point of the table. As I approached, the rock was

laced with fissures. Some were only just visible, others were several feet

across and I had to detour to get around them. I looked down into them, and was

unable to see the bottom. I kept thinking of Wiley E. Coyote cartoons.

The view was worth the hike. You could see to the horizon in all directions.

To the west, the hills of Algeria were within spitting distance. I hoped no

bands of foreigner-killing terrorists were roaming on this side of the border

today. But that wasn't a real worry.

I climbed down again. At the base of the Table, I saw a Tunisian couple walking

up, either tourists or shepherds. I waved.

Walking around the base of the Table, back to my car, I kept running into flocks

of sheep. They were quite alert and would stop and look at me carefully before

deciding I wasn't a threat. A pair of sheepdogs decided I *was* a threat,

fortunately the shepherd nearby called them off.

I made my way back to the car, and headed off again. My destination now was

Sbeitla, home to the ruined Roman city of Sufetula.

Driving to Sbeitla (14 Feb)

On the way through a small town, another policeman waved to me. I pulled over.

I saw that in fact the policeman was wearing a casual coat--he just needed a

ride to work. I figured that was pretty safe, if not safer than travelling

alone.

His name was Mahoud, and he was going to Sbeitla as well, which was convenient.

We talked quite a while (it was close to an hour and a half journey), and he

gave me some lessons in French. He (like Smith, the Ghanan in Tunis) had a

pretty good grasp of the US political scene. He asked for my opinions on Bush

and Gore and the elections. He even made a Monica Lewinsky joke. Having a

Tunisian policeman make a joke in French about Monica Lewinsky as we drove

through the dusty plains north of Kassarine struck me as so improbable that I

laughed far harder than the joke deserved.

At one point, we were stuck behind a truck piled high with sheep. And they were

literally piled, one on top of the other, stuck together uncomfortably like a

scene from Wallace and Gromit. I made a comment to Mahoud.

"Yes, there is a festival coming up." I nodded, I had read about that, it

coincided with the mass pilgrimage to Mecca, the Hajj. "On that day, the

sheep..." he made a slitting motion with a finger across his throat.

Sure enough, the idea is that everyone grabs a sheep and sacrifices it at the

same time. Kind of like that Far Side cartoon where the professor realizes he's

the only one at the seminar without a duck.

The book mentioned that the "streets of towns and cities seem to run with the

blood of slaughtered sheep." That seemed like a melodramatic exaggeration, but

having seen the vast amounts of sheep around, now I'm starting to believe it.

I'll be out of the country by then in any case.

Still, if you're in the country around the end of February, that's something to

look forward to. Although now that I think about it, the festival probably isn't

tied to the Gregorian calendar.

The Ruins at Sbeitla (Sufetula - 14 Feb)

Once in Sbeitla, I dropped Mahoud off at the side of the road. I needed no

directions to the ruins: the three central temples stood quite clearly in the

afternoon sun.

As on the day before, I was starving. Mahoud had pointed me down a side road

where he claimed a shop lay in wait. Sure enough, I found one. The owner

expressed a split-second of shock when I entered, then was all business. It was

a common reaction in the small towns.

I was a good customer. Bread, water, cheese, yoghurt, chocolate. I stuffed

everything in my travel bag, and walked into the ruins.

Had I never seen Dougga, I would have been blown away. Even having seen Dougga,

I was impressed. There were wider streets here-either Sufetla was bigger, or it

was easier to build wide roads on plains than hills.

Walking among Roman houses, you are struck by how small everything is. Small

rooms. Small atriums. Narrow roads. Even the main roads are narrow by

today's standards. But you walk into modern (i.e., inhabited) medinas, and you

see the same thing.

The graceful columns, the straight roads, the temples, the baths, the arches--

they inspired awe, humility, and respect.

I took a wiz behind a tree, and ate lunch sitting among the ruins of a bath

house. To my left was an almost completely intact mosaic, the floor of the

main hall of the baths.

After eating and relaxing in the sun, I walked to the north end of the complex.

I passed houses, temples, more baths. In one house I saw a mosaic in a kitchen,

the floor covered by centuries of dust. I was relieved to know that in all the

world there was at least one kitchen floor dirtier than mine.

I walked back to the three temples at the heart of the ruins. Temples to

Jupiter, Minerva, and Juno stood shoulder to shoulder above the Forum. The

guidebook mentioned that the temples looked best at dawn, here they looked quite

dignified in the long shadows of sunset.

There was a theater by the river. It had been restored recently, new concrete

and stone mixed with the ancient rock. I was going to ask a guard if they used

the theater now, but he had disappeared. So if you ever find yourself in

Sbeitla after 5, you can probably get into the ruins for free.

The arch at the southern end was fully intact, the best-preserved artefact I'd

seen on my trip.

Driving to Sfax (14 Feb)

Then it was on to Sfax. I was hoping to make it before nightfall, but as I left

I realized that was hopelessly optimistic.

At the south end of Sbeitla, the road swarmed with soldiers. Apparently they

were done for the day, soldiers had dispersed and were looking for a lift home.

I stopped for one, and he indicated he had a friend going the same way. So both

piled into my car. The one in front (the first one I'd stopped for) was Jemel,

I didn't catch the name of the other. We all spoke a bit of French. We had the

standard conversation: Where are you from, how long in Tunisia--only a week?

You should visit here, here, here...

Jemel said he had worked with Americans in Bizerte only a few months before. I

don't know in what capacity, but he said the Americans were "bon, tres bon."

I dropped off Jemel and his friend at various points, and continued on alone.

The road was in the best condition of any I'd seen. It was a real pleasure,

flying through the Tunisian countryside at twilight. I passed miles and miles

of olive trees.

As it got darker, pedestrians became a real hazard. Schoolchildren would walk

in the road. At one point, a bus was letting people out by the side of the

road, and young men were crossing the road oblivious to the traffic, obscured by

the dust. Drivers honked and flashed their high beams, but to no avail.

I had a realization--the vast majority of Tunisians (particularly in the

countryside) didn't drive. They had no idea of what it was like behind the

wheel, or what danger they were putting themselves in. A revelation, but it

didn't make the driving any easier.

I arrived in Sfax, and now had to deal with an unfamiliar Tunisian city in the

dark. As in all Tunisian towns and cities, there was a chaotic grid of streets,

most of which were one way. I drove around for a while to get my bearings. I

finally found my hotel, recommended by the guidebook. It was built by the

French in 1923. Even now, almost eighty years later, it was supposed to be

luxurious and dignified, though faded somewhat from its former glory.

The building was indeed magnificent, taking up an entire city block. Palm trees

stood silently in the courtyard.

Sadly, it was completely gutted. It must have closed since my guidebook was

printed, and was in the process of being torn down (or was simply being

abandoned, which seems to happen a lot in Tunisian cities).

So I drove to my second choice, a far less fashionable but still comfortable

hotel near the medina. The guidebook was wrong here as well, but in my favor--

the rates were half of what I was expecting.

A Day in Sfax (15 Feb)

I went to bed early, and slept late. I had breakfast just past 9, and was the

only one eating in the large restaurant. I think there were many other guests,

but they had eaten at a more respectable hour.

I was shocked to realize that it was my last full day in Tunisia. I had

mentally prepared for two days in Sfax, but the earlier trip to Carthage and

Sidi Bou Said had cost me a day. In retrospect, that was time well spent.

I debated driving up to El Jem, but decided not to. This was a day to relax.

The medina at Sfax was picturesque--"The English Patient" was filmed here. I

spent several hours walking through town.

I found an Internet cafe, the first I'd seen in Tunisia (although I'm sure there

are some in Tunis). I checked in with friends and family, and followed up on

some job leads.

When I left, the young man at the desk asked me what languages I spoke. He was

delighted that I spoke English, he wanted to practice. It was the same

conversation: Where are you from, how long in Tunisia...

Still, this was a far cry from the dubious hustlers in Tunis. Since I had left

Tunis, I had encountered nothing but friendly, sincere people. I can return to

Tunis with the knowledge that the inhospitable environs of Avenue Habib Bourgiba

are not representative of the country as a whole.

I was pestered by one hustler in Sfax, in the new town. I walked through the

medina several times without being pestered at all. I can see why the guidebook

recommends Sfax. I had to walk across town to find the restaurant, I never felt

uncomfortable.

Sfax is not someplace I'd want to spend a lot of time. The waterfront is remote

from the city, and when I walked for an hour in an attempt to reach the

Mediterranean, I was greeted by an intimidating fence and a sign with a maniacal

soldier holding a gun. The sign was hilarious, I would have taken a picture but

there was another sign saying no pictures, which I chose to obey given the

maniacal soldiers.

I did find a stretch of waterfront, next to the guardhouse (with the fence). It

was next to a dump, fortunately a fresh breeze blew in from the sea. I put my

hand in the water, so at least on this trip I managed to touch the

Mediterranean.

I had lunch in the cool shadows just inside the gate to the medina.

I walked back to the hotel and crashed. I'd been fighting a cold since I left

Istanbul, today it was threatening to take the upper hand.

After a few hours sleep, I wrote for a few more hours, then went out for dinner.

The hotel restaurant was alive with tourists, but I wanted to see the city

again, even if only at night. I walked across town to a small French place.

The restaurant had simple fare (luckily it had something besides omelettes for

vegetarians), but was the best meal I'd had in Tunisia.

I walked back from the restaurant, and took some pictures of the medina walls.

A policeman approached me with a look of annoyance.

"This area is very dangerous."

"Really?" I was genuinely shocked.

"Where is your hotel?"

I told him. He grunted, indicating that it was close enough that I would

probably make it back in one piece. He wished me a good night and walked on.

I saw more policemen as I walked back to the hotel. Perhaps it was a slightly

dangerous area. I walked back to the hotel, and went to sleep. I had to get up

very early the next day if I was going to see El-Jem and still return the car by

noon.

There is only one thing worse that sharing a hotel floor with a group of

excitable French teenagers: sharing a hotel floor with a group of excitable

French teenagers that play the bongos. Oddly enough, that's exactly what I was

doing. The previous night had been rather quiet, but tonight they kept running

up and down the halls, knocking on doors, and (surreal, I know) playing the

bongos. They finally quieted down around 4am, so I had around an hour of solid

sleep.

The Colisseum at El Jem, and Tunis (16 Feb)

When I checked out the next morning, the receptionist recoiled in fear from the

Visa card I profferred.

"Cash only, sir," he said.

So I had to drive out and find a cash machine (there were none near the hotel).

I was on the road to Sousse just before 8 o'clock, about an hour later than I

wanted. I kept the spedometer pinned until I reached El-Jem.

I came over a hill, and the colisseum of El-Jem was laid out before me. The

road ran straight towards it: as with most of Tunisia's highways, it was built

on top of the old Roman road.

I spent longer than I intended at the colisseum. I think it was smaller than

the colisseum at Rome but even so it was impressive, and much of it was still

standing. Much of the underground complex was still intact. The place was also

quite busy with tourists, which after everywhere else I'd been in Tunisia, was a

novelty.

After the Colisseum, I sped north to Tunis. The last 200-250 km were over a

two-lane highway, one of the few in Tunisia. The speed limit was 100 km/h, but

I (and most of the other traffic) drove closer to 140.

I stopped at a petrol station just inside Tunis, and asked them to fill the

tank. It had cost around 20 dinars before, I figured it would again. Instead,