| < | Wavepacket Blog |

> |

| << Newer entries << | |

| 2010 | |

| May | |

| Fri May 7 22:44:43 2010 Tree-Hugger Me |

|

| April | |

| Tue Apr 6 22:25:15 2010 Gene Patents |

|

| January | |

| Sun Jan 10 23:20:41 2010 Why was there a worldwide recession? |

|

| >> Older entries >> | |

| >> links >> | |

| Fri May 7 22:44:43 2010 Tree-Hugger Me I'm a die-hard environmentalist in spite of my SUV. |

|||||||||

| Today I celebrated 6 weeks of commuting to and from work without driving!

This is all because I recently moved (see The Dream Tour), and I can bus to work and walk to almost everywhere I need to shop. I've been mostly commuting by public transit since December, but in March my parking pass ran out so I've been commuting 100% car-free since then. My gasoline consumption has dropped by around 50% or more compared to 2009, even though I often drive into the mountains on the weekends. However, I still drive a large black SUV that gets really crappy gas mileage. So I can't really call myself an environmentalist, can I? Well, actually I can and I do. I was inspired by this story, which pointed out that most people think about environmentally-friendly driving entirely wrong. Most people think that we can help the environment by buying cars with better gas mileage. But as the article noted:

So by moving and driving far less, I've actually reduced my carbon footprint much more than had I stayed where I was and bought a Prius. Don't get me wrong, eventually I'll get a greener car. But it won't be a Prius. It will be an SUV that has cleaner emissions. I need a truck with clearance, room for cargo and gear, and four wheel drive. That's another thing many people (including proclaimed environmentalists) get wrong, by the way. When it comes to the environment, gas mileage isn't important: emissions are important. The two are related, but they don't have to be. Car and truck manufacturers could be held to much stricter emissions than they are now. Paradoxically, better catalytic converters could slightly reduce gas mileage, but that would be overall worth it. So what is the responsible, green future for the planet? It won't be suburbia with hybrids. It will be people living much closer to where they work and shop, driving far less, in cars that have about the same gas mileage as now, but with lower emissions. That's going to be a big demographic shift, but it will be better for the atmosphere, and will also be forced by rising gasoline prices. Comments |

Related: economics science environment predictions Unrelated: books energy geopolitics lists mathematics |

||||||||

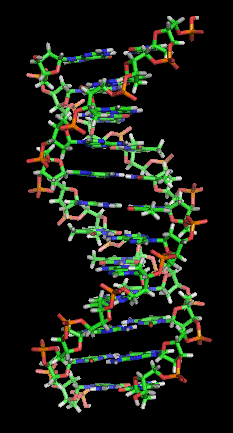

| Tue Apr 6 22:25:15 2010 Gene Patents A surprising verdict that could change everything. |

|||||||||

| What with the

passage of the healthcare bill,

the recent strategic armaments treaty, and

earthquakes, an important story was mostly buried this week. The story, which is

causing an uproar among biologists, is that

the ACLU has just won a lawsuit which

invalidates several gene patents.

This article has a great overview of how the case unfolded.

This is big news. Why? On the one hand, many people are worried that by blocking patents of human genes, companies and institutes will be unwilling to investigate genetically-targeted (or inspired) drugs. For instance, the Northwestern University report quoted above includes a quote from one lawyer:

that is, because patents won't be filed, companies will keep genetic sequences private. However, that same article quotes other practicing scientists as saying

and also notes independently that

[Myriad Genetics was the defendant in the lawsuit, and their BRCA breast cancer test relied in part on patents on the human BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.] I'm with the scientists on this one. Allowing patents of standard human gene sequences is dumb and contrary to the spirit of patents. It was a mistake to have allowed it in the first place, and the ACLU was right to challenge it. Is this the end of patents for biotech? No. Even the scientists who supported the lawsuit noted that

In short, companies can patent anything they invent that is original, but can't patent Mother Nature. It is early days still! The result will almost certainly be appealed. But I am hoping that higher courts will uphold the verdict. If so, I think we'll see even more genetic information publicly available, which should speed cures and lower costs for everyone. Comments |

Related: economics science Unrelated: books energy environment geopolitics lists mathematics predictions |

||||||||

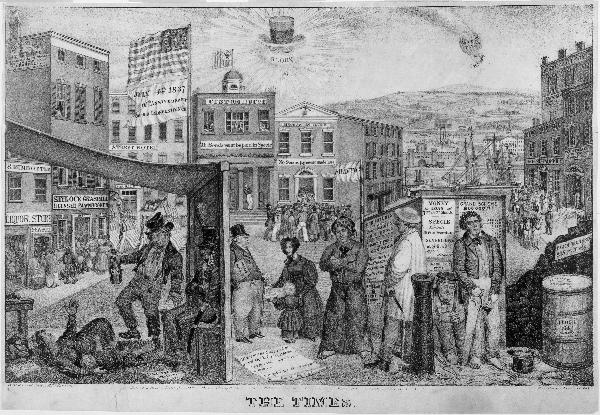

| Sun Jan 10 23:20:41 2010 Why was there a worldwide recession? Oddly, no one agrees on this. Worse, no one agrees with me. |

|||||||||

| I happened to be reading through

Slate, one of my favorite websites. I saw that they had an article covering

the 15 best explanations for the Great Recession.

The author's contention is that although most people seem to agree that the mortgage collapse precipitated the crisis, no one agrees on why the fallout was so bad. Jacob Weisberg's conclusion: our financial markets need stronger regulatory supervision and better controls to prevent bad bets by big firms from going viral Usually I like Slate, but this time they seem to have watered down the subject matter so much that the article is actually misleading. To be fair, Weisberg was writing the article for Newsweek (sorry, couldn't resist the jab). Saying "the reasons for the recession are very complicated" and "the solution is more regulation" is basically a capitulation. The author is admitting that he doesn't actually know what went wrong, but is sure someone does, and that someone will regulate things better so that this never, ever happens again. Of course, they said that in the Panic of 1837, the Panic of 1857, the Panic of 1873, the 1882-1885 recession, and... well, you get the idea. If you didn't get the idea, you can peruse Wikipedia's list of US recessions. Don't get me wrong, I'm not a laissez-faire capitalist. Directed regulation is effective and required. But on the other hand, I'm not a wild fan of wishful naivete either. Vague hopes that increased regulation are going to somehow prevent future recessions are frankly stupid. At least admit that you don't know what went wrong, and don't try to fix things until you do. Being all-knowing, or at least partially knowing and both tired and cranky, I can offer my own suggestions. The first step in understanding what went wrong is to remember that, unlike what most columnists are saying, the root cause of recessions is pretty straightforward. Why do recessions happen? Generally, because people spent more money than they actually had. That's called a boom period. Then the bills show up, people realize the assets they were counting on weren't worth as much as they thought, and prices and spending generally contract for a while as everyone sorts out the mess. You can change the exact flavors of the day, but that's basically it. People spend too much, either because of cheap money (interest rates too low) or overvalued commodities (mortgages not properly valued for risk), and then when reality hits they have to spend less for a few years to even everything out. And boom and bust cycles will always be around, because accurate valuation for anything is very hard and even honest, diligent people get it wrong most of the time. So that's part of the problem (or the reality). Boom and bust cycles will always be here, and therefore, there will always be recessions of some kind or another. So what does regulation do? More importantly, why is regulation around? Regulation exists for only one reason: to reduce risk. A great example is the regulation banks must undergo for FDIC insurance. Having FDIC insurance is great for depositors, but a bank can't promise that to customers until they first prove to the FDIC that they are running a low-risk operation. The government can't insure accounts if the risk is too high. And don't fool yourself: regulation cannot remove risk. Even the most stringent accounting and ethical behavior can't protect a company from competing innovation, freak weather, or an asteroid impact. All regulation can do is attempt to reduce risk. And if regulation can only reduce but not eliminate risk, then recessions will continue to happen. So why was this recession worse than most others, historically speaking? One reason, I think, is the repeal of the Glass-Steagall act. I'm not a banking expert, and I certainly don't commonly quote banking regulations. But I keep coming back to this one. The Glass-Steagall act was passed in 1932 to keep banks simple. The act said that commercial banks (where people and businesses keep their accounts) cannot engage in investment banking (where the bank uses peoples' deposits to fund speculative investments). As I said, that was repealed in 1999 and now there are no distinctions between commercial and investment banks (at least in this sense). Your bank can take your savings account and invest it in speculative ventures. So when the Aughties Recession (or the Great Recession) started, more of the nation's money (our savings accounts) were exposed. Whether it was an over-reliance on new mortgage securities or otherwise, the large amounts involved meant more people's cash was at risk, and more money was frozen when people were afraid to sell. So what is my solution? Keep regulation simple. Re-instate the Glass-Seagall act, and regulate commercial banks with simple (or at least standard) accounting and financial instruments. Most importantly, guarantee all money that is regulated. And if you're not going to guarantee an institution or account, don't regulate it. That tends to be a great focuser. Require honesty and accuracy in accounting in all banks and companies, but don't pretend to certify that high-risk investments are safe or understood. Instead, make the risks known and make sure everyone knows which accounts are guaranteed, and which aren't. Comments |

Related: economics Unrelated: books energy environment geopolitics lists mathematics predictions science |

||||||||

| Links: |  |

Blog Directory | Blog Blog | Technorati Profile | Strange Attractor |