| < | Wavepacket Blog only displaying 'economics' posts |

> |

| << Newer entries << | |

| 2008 | |

| June | |

| Tue Jun 3 22:38:01 2008 Fooled By Randomness |

|

| May | |

| Wed May 28 23:05:03 2008 Seizing Up Explained |

|

| Mon May 19 23:06:50 2008 More Bad Gas |

|

| >> Older entries >> | |

| >> links >> | |

| Tue Jun 3 22:38:01 2008 Fooled By Randomness A book report. |

|

| I recently read (well, re-read) Nassim Taleb's

Fooled By Randomness, subtitled "The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and the Markets."

It is an excellent book, well-worth reading for two reasons:

I had two main take-aways. The first take-away was a deeper appreciation for the Survivor Bias, which occurs when a supposedly statistical study fails to include all data properly. In finance, it is common to compare only long-lived mutual funds (for example) and ignore all of those that have failed. It is very sobering to realize that if you put a bunch of people and funds into place, had them guess randomly about investments and tracked them over time, you would see many fail and a few survive for a long time (by chance)--exactly the same situation we observe today! Only we don't say long-lived or successful funds are random survivors. We say the fund managers are geniuses, and expect them to repeat their successes. (Again, soberingly, most don't). The second take-away was people's poor appreciation for probability. Even in his world of trading, where people with scientific and mathematics backgrounds were working on algorithmic strategies, there was a disconnect with simple statistics. Even basic concepts such as Expected Value were often missed! Nassim's main point was that a person well-versed in basic probability, and aware of the large role of randomness in the world, could avoid many common mistakes and maybe even make money off other peoples' ignorance. Certainly that's true in his profession. It isn't a perfect book. He extended some of the survivorship bias to good people management. I think enough of us have had good (and bad!) managers to know that good managers often aren't survivors--they are actually good managers. I see Nassim's point that sometimes managers get lucky (due to happening to manage an organization during a moment of critical success or riding a market bubble, etc.), so a few "star" CEOs may actually be just average managers who happened to be at the right place at the right time. But some of his arguments here felt a bit jaded. Still, an overall enjoyable read, and a good reminder while the markets are in their current volatile state. I don't know how Mr. Taleb did in the subprime mortgage crash, but given his stated preference for targeting large crashes, I suspect he did quite well. Comments |

Related: > economics < mathematics books Unrelated: energy environment geopolitics lists predictions science |

| Wed May 28 23:05:03 2008 Seizing Up Explained What seizing up really means, and why you should be afraid... |

|

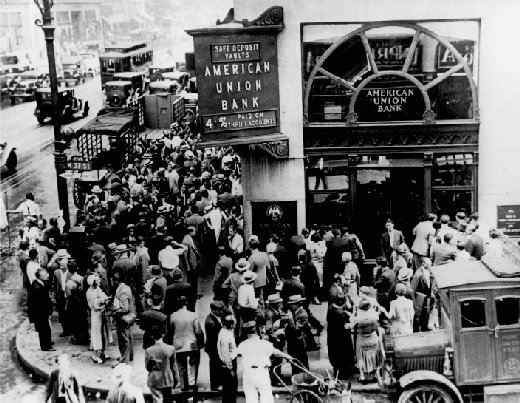

| There was a good story in today's

Wall Street Journal. It covered the last few days of

Bear Stearns' life as a solvent company. It was fascinating reading!

One thing really struck home: the speed of the collapse. Once investors realized Bear Stearns had problems, they rushed to pull out their investments, and banks who were lending them money notified them that their loans wouldn't be renewed. The result? As you'd expect, Bear Stearns ran out of money fast. They couldn't raise the capital necessary to return investor funds, especially since banks were refusing to lend them any more. All they could do was sell their existing securities at fire sale prices to try to pay back investors. This is the classic description of bank runs, even though this was a investment bank rather than a commercial bank. I've written before about the rampant use of the term "seizing up" to describe the post-subprime collapse (see Carpe Seize! or Seizing Up). I was curious, what can they (reporters and financial pontificators) mean by "seizing up?" The WSJ Bear Stearns story is pretty clear: the entire investment bank community was primed to collapse. Investors everywhere would realize "hey, these investments aren't safe at all!", and they would all try to pull their money out at once. Investment firms would not be able to return the funds, because they don't have any. All of your invested money has been used as collateral on loans for the investment banks to make other, bigger investments in an attempt to make high returns. If everyone demanded their money, the firms would be forced to terminate their positions, probably at a loss, in order to close out the loans and return funds. Because all of the investment banks would be selling their securities at the same time in order to raise cash to return to investors, prices would plummet, and the result would be that most of the firms would go under (massive losses amplified by leverage) and most investors would get back only a fraction of what they'd put in. That's what I think "seizing up" means. The house of cards would really collapse. Rather than let that happen, the Federal Reserve moved to keep investment banks solvent. In an unprecendented move, the Fed helped broker a deal whereby JP Morgan would buy Bear Stearns at a huge discount, with the Fed promising to cover all Bear Stearns losses with taxpayer money (see the stories at MSNBC and CNN). I think that is a bad idea. The Fed is trying to cover investment banks with the same guarantees as commercial banks. But that is bound to fail. Why is the Fed's move to protect investment banks ultimately doomed to fail? Because investment banks are competing for the highest rate of returns. The way to achieve high returns is to take on high risk. And that means taking leveraged positions in the market. By attempting to guarantee investment banks, the Fed is putting billions of taxpayer dollars at risk. I say billions, because although the Fed is putting trillions of taxpayer dollars at risk, that is only on paper. A bad crash would bankrupt the country well before we reached the trillion-dollar mark. So what should the Fed do? The Fed should continue to cover and regulate commercial banks. Also, it should only protect commercial banks. Since the 80's, the Fed has let commercial banks take on investment bank responsibilities, especially with the Gramm-Leach-Billey Act, which I'd never heard of before but now looks very suspicious. Once the Fed is back to protecting commercial banks, it should be clear with investors: "If you choose to invest with investment banks, be aware that your deposits are NOT insured, and you could lose all your money." Right now, even a conservative investor is a fool not to invest in risky investment banks. There is no downside. If the bank does well, you make money. If the bank collapses catastrophically, the government will bail you out. So why not take a lot of risk, and let other taxpayers bail you out if needed? If the Fed persists in attempting to cover the risky behavior of investment banks, we'll be fine until the next market crash. Then the result will either be collapse of the economy (unlikely) or the currency (very likely). The currency will collapse as the government realizes it needs to print more money to cover all of the investment bank losses. Comments |

Related: > economics < Unrelated: books energy environment geopolitics lists mathematics predictions science |

| Mon May 19 23:06:50 2008 More Bad Gas Congress and the President pass a bad law. |

|

| Today President Bush

signed into law a dubious bill submitted by the US Congress. It was another attempt

to reduce oil prices, and it may have serious consequences. (See

High Oil and Gas Prices for another even less effective Congressional attempt).

Senators had noticed that the US Strategic Petroleum Reserves were buying 70 thousand barrels of oil a day. Their thinking was that stopping these purchases would help reduce demand and therefore prices. Don't get me wrong, I hate high gas prices. I just filled my tank today and I was stunned (prices here are now well over $4 per gallon). I'd like prices to come down. However, the Congressional bill was ill-advised for two reasons: First, the strategic reserve purchases are a miniscule part of total demand. The United States consumes over 20 million barrels of oil a day. The 70 thousand barrels amounts to 0.3% of total US demand. Not 3%, 0.3%. Furthermore, oil is a global commodity, so the impact has to be judged relative to global consumption. The world consumes over 80 million barrels of oil a day. So the US Congress has removed less than 0.1% of global demand for oil. It is unlikely that the global markets will even notice that tiny drop in demand. But let's say the markets do notice, and the price drops by 0.3% (I've generously multiplied the demand drop by 3 since oil is after all an inelastic supply). In the best, most generous case, Congress may have reduced gas prices by one penny. Hey, maybe that's worth it, right? Wrong. That brings me to my Second reason that the Congressional bill was ill-advised: Congress is assuming that we are in a temporary period of high oil prices. Halting strategic purchases would help ameliorate the high prices, and then the purchases can resume when prices come down a bit. (The bill--now a law--stipulates that purchases can resume again at the end of 2008). However, there is a very good chance that prices will keep rising for the foreseeable future. Why would prices drop, after all? Demand won't drop very quickly, since a demand drop will require that large numbers of American consumers and industries replace their inefficient cars and factories with more efficient models, which will take a long time. (Based on the 1970's oil shock, it takes several years for demand to come down). But even if US demand is dropping, other world demand (China, India, others) continues to accelerate. A drop in US demand would help a lot, but this isn't the 1970's anymore. There are a lot more industrialized countries to buy that oil. And oil production is peaking. Russian oil production peaked in 2007, leaving only OPEC countries to keep up with production. However, only Saudi Arabia has significant reserves, and they are running out of easy-to-extract oil. Oil industry observers know all this. They expect prices to rise, not decline. Goldman Sachs recently predicted that oil prices would reach over $140 per barrel in 2008, up from close to $130 today. And they predict prices in the $150-200 range in the longer-term (6 months to 2 years). That would mean gas prices well over $6 per gallon. So what did Congress actually accomplish? We've saved a penny per gallon now (maybe), and then the strategic reserve will have to start buying again later when gas is even more expensive. And if you believe that stopping the purchases helped prices now, then you have to agree that starting the purchases later will hurt prices then. Comments |

Related: > economics < energy Unrelated: books environment geopolitics lists mathematics predictions science |

| Links: |  |

Blog Directory | Blog Blog | Technorati Profile | Strange Attractor |